Hausa Verb Tense

Meaning and Marking of Hausa Tenses

Overview

- Seven “tense” distinction plus imperative

- Completive

- Continuative

- Future

- Subjunctive

- “Indefinite” Future

- Habitual

- Imperative

- The primary marking of “tense” distinctions resides in subject pronouns, NOT verbs

- Two “tenses”–Completive and Continuative–distinguish a “plain” and a “relative” form: a major factor determining this distinction is whether or not something preceding the verb is questioned, emphasized, or relativized

| Kafin ka dawo, yaranka duk sun girma. | ‘Before you come back, your children will have all grown up.’ |

| Audu ya ci k’osai maimakon yaci waina. | ‘Audu ate bean cakes instead of eating millet cakes.’ |

| Ya yi tafiya ba hutu balle ya ci abinci. | ‘He traveled without a rest much less did he eat food.’ |

Technical note on tense, aspect, and mood

“Tense” is not really the best term to describe the sorts of concepts that Hausa verbs convey. The term tense comes from Latin tempus ‘time’, and in Western European languages, distinctions having to do with time are the main distinctions that verbal differences mark. In Hausa, and most other African languages (as well as many other languages throughout the world), marking the time of an event is not a primary function of the verbal system–context or words such as time adverbs (‘now’, ‘earlier’, ‘tomorrow’, etc.) are the means to locate events in time.

A more appropriate term for most of the distinctions that Hausa verbs convey would be “aspect“. This term comes from Slavic linguistics, where verb marking focuses on whether events are viewed as being complete–not in a state of flux–or incomplete–in progress or otherwise conveying a sense of change. The most fundamental distinctions that Hausa verbs mark are of this type. The traditional terms for these concepts are perfective and imperfective respectively. Over the years, I have preferred these terms over other terms for Hausa because they have a solid precedent in Slavic and general linguistics, and being a believer in linguistic universals, I prefer to adopt terms that have already been applied to particular distinctions rather than to invent new terminology for each language, somehow giving the impression that that language has special properties not shared across languages.

Nonetheless, after years and years of trying to force these terms down the throats of non-linguist Hausa students, for whom the terms were meaningless and opaque, I have decided to let linguistic accuracy give way to common sense and practicality for the non-linguist student of Hausa. I therefore use the following terms:

- Completive = Perfective (Note that calling this “Past” tense is absolutely wrong! There are past events that Hausa does not mark by Completive and there are Completive events that are not past.)

- Continuative = Imperfective (Note that calling this “Present” tense is absolutely wrong! There are present events that Hausa does not mark with the Continuative and Continuative events that are not present.)

- Future (not quite like European language future, but close enough!)

- Subjunctive (I find this to be a pretty good term, based on the Latin etymology meaning joined under, since nearly uses of the Subjunctive are dependent on some preceding verbal or verb-like construction.)

- “Indefinite” future = “Second” future (“Indefinite” to refer to this form is not a great term, but it is descriptive enough of its functions to serve the purpose.)

- Habitual (Basically an accurate characterization of the function.)

Strictly speaking, Subjunctive, “Indefinite” future, and Imperative (which functions as a direct command, like imperatives in essentially all languages) are moods, i.e. they convery something about speaker attitude. It has always seemed to me that “mood” is a superfluous distinction when describing verbal forms, since it is a semantic notion which, in general, overlays the more fundamental concepts of tense or aspect, depending on the language. I do not use the term “mood” in this grammar.

Technical note on the term “relative”

I have adopted the term “relative“, the traditional term in Hausa linguistics, to refer “Relative Completive” and “Relative Continuative”. This is an exceptionally poor term for these forms since it draws attention to only one function for these forms: the relative clause function. (Some linguists have been mislead by the term itself, trying to interpret all contexts where it occurs as somehow deriving from relative clauses!)

I would personally prefer a term like “Definite” Completive/Continuative, or “Presupposed” Completive/Continuative, but these terms would probably be opaque as to function and too narrow as well. Over the years in teaching Hausa, I have usually referred to the two Completives as the sun and suka forms and the two Continuatives as the suna and suke forms, these being the third person plural subject pronouns for the respective distinctions. However, this leads to confusion if one is describing the verb in a sentence like na zo ‘I came’ as using the “sun” form as subject, when “sun” means ‘they’ and the subject of the sentence is ‘I’!

I have therefore given into tradition, which at least has the advantage of making the description here consistent with most other descriptions of Hausa.

Meaning of Tenses

English and most other European languages have what is called absolute tense. This means that simply by knowing the tense form of a verb, you know the basic time of the event. If you use a verb in past tense, the action already took place (it is past with respect to the time of speaking). Likewise, future tense means that the action has not begun at the time you are speaking, and present means the action is happening at the time you are speaking.

In the absence of any context to the contrary, Hausa tenses can have similar meanings to those of English, e.g.

| Past | They entered. | Sun shiga. |

| Future | They will enter. | Za su shiga. |

| Present | They are entering. | Suna shiga. |

But Hausa has what is called relative tense. This means that the tense form tells you about the time of the event relative to some time of reference. If no time context is mentioned, the assumption is that the time of reference is the moment of speaking, as in the examples in the table above. However, if the time of reference is displaced to the past or the future, English (which has absolute tense) must change the tense marking, whereas Hausa continues to use the same forms as in the table above.

| Past (past context) | Yesterday by 3:00 they had entered. | Jiya da 3:00 sun shiga. |

| Past (future context) | Tomorrow at 3:00 they will have entered. | Gobe da 3:00 sun shiga. |

| Future (past context) | Yesterday at 3:00 they were about to enter. | Jiya da 3:00 za su shiga. |

| Future(future context) | Tomorrow at 3:00 they will enter.* | Gobe da 3:00 za su shiga. |

| Present (past context) | Yesterday at 3:00 they were entering. | Jiya da 3:00 suna shiga. |

| Present(future context) | Tomorrow at 3:00 they will be entering. | Gobe da 3:00 suna shiga. |

*English continues to use the simple future since the event is in the future regardless of whether a future context is expressed or not.

Marking of Tenses

English marks tense by changes in the verb form (enter vs. entered vs. entering) and/or addition of auxiliary verbs (have, had, will, are, were, etc.). In Hausa, for the most part, the verb itself does not change to mark tense differences. Hausa marks tense differences by different sets of subject pronouns, sometimes with the pronoun combined with some additional particle, such as preceding za, which marks future (see the table above). For this reason, a subject pronoun must accompany every verb in Hausa, regardless of whether the subject is known from previous context or is expressed by a noun subject. Here are some examples:

| Na shiga na zauna. | I entered and sat down. (“I entered I sat down.”) |

| Yara sun shiga sun zauna. | The children entered and sat down. (“Children they entered theysat down.”) |

| Muna hira muna dariya | We are chatting and laughing. (“We are chatting we arelaughing.” |

| Yara suna hira suna dariya. | The children are chatting and laughing. (“Children they are chatting they are laughing.”) |

(Notice that although Hausa requires a subject pronoun with every verb, it does NOT have a word like “and” between consecutive verbs.)

“Active” vs. “Stative” Verbs

“Active” verbs represent some kind of action, such as run, enter, eat, take–in fact the large majority of verbs. “Stative” verbs represent a state of being, a mental state, or a static relationship, such as be-nice, know, see, be-older-than.

In English, using an active or a stative verb has an effect on choice of tense.

| Active verb | Stative verb |

| John is drinking tea. | John sees the tea. |

| John is doing something–he is engaged in an ongoing activity. | The tea is in John’s line of sight and is registering in his brain–he is not “doing” anything. |

| English uses the present progressive (a form of ‘be’ + the -ingform of the verb). | English uses the simple presentform of the verb. |

In Hausa, the “active” vs. “stative” sense also determines choice of tense.

| Active verb referring to present time | Stative verb referring to present time |

| Bashir yana shan shayi. ‘Bashir is drinking the tea.’ |

Bashir ya ga shayi. ‘Bashir sees the tea.’ |

| Bashir is doing an action. | The tea is in Bashir’s line of sight and is registering in his brain–he is not “doing” anything. |

| Hausa uses the Continuative, which shows an event that is unfolding over time. | Hausa uses the Completive, which shows that the event is viewed as a “unit”, i.e. the effects of the event are complete. |

English and Hausa differ, however. The Hausa Completive with a stative verb translates as English Present, but the Completive with an active verb usually translates as English Past tense. This is because the base meaning of the Completive is that the event is viewed as “complete”, i.e. its effects are no longer in a state of flux.

| Active verb with Completive | Stative verb with Completive |

| Bashir ya sha shayi. ‘Bashir drank the tea.’ |

Bashir ya ga shayi. ‘Bashir sees the tea.’ |

| Bashir has completed the tea drinking. | Bashir’s mental picture of the tea is complete–it is not evolving from one moment to the next. |

| The translation into English uses a Past tense, showing that the event came to an end at anearlier time. | The translation into English uses a Present tense, showing that the seeing is in effect at the present moment. |

Completive

Basic Meaning of Completive

Hausa has three “Completive” forms, but they share a basic meaning:

- The Completive indicates that the event expressed by the verb is viewed as a “complete unit”. That is, it is complete at the time referred to and is no longer in a state of flux.

- English translation with an active verb will usually be past tense, e.g. sun zo ‘they came’.

- English translation with a stative verb will usually be present tense, e.g. sun sani ‘they know.’

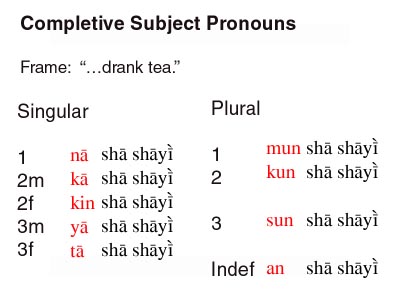

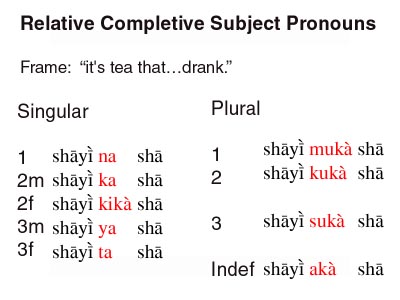

The table below illustrates the three Completive forms, each with an “active” verb and a “stative” verb. Click the highlighted links to see full pronoun paradigms.

| Active verb | Stative verb | |

| Completive | Sun sha shayi. ‘They drank tea.’ |

Sun tuna malaminsu. ‘They remember their teacher.’ |

| Relative Completive | Me suka sha? ‘What did they drink?’ |

Wa suka tuna? ‘Who do they remember?’ |

| Negative Completive | Ba su sha shayi ba. ‘They didn’t drink tea.’ |

Ba su tuna malaminsu ba. ‘They don’t remember their teacher.’ |

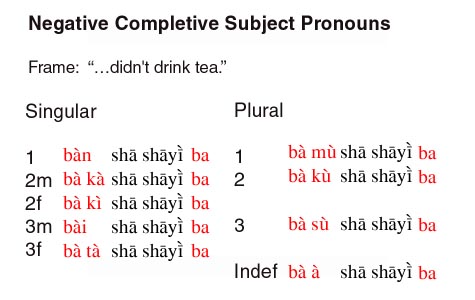

Forms of the Completive

As with all Hausa tenses, the tense is marked by the form of the subject pronoun rather than by the form of the verb. Hausa has three Completive forms, whose functions are explained immediately below. The bases for forming the Completive pronouns are as follows. Click on the highlighted links to see the full paradigms.

| Completive | Relative Completive | Negative Completive |

| – 2nd fem. sing. and all plurals: pronoun ends in -n

– all others: pronoun ends in long -a |

– 2nd fem. sing. and all plurals: pronoun ends in -ka

– all others: pronoun ends in short -a |

ba + pronoun + Verb … ba

(pronouns all have Lo tone and short vowel) |

Uses of the Three Completive Forms

The three completive forms share the basic meaning described above. The differences have to do with the contexts in which you wish to express that meaning. Below are lists of the main uses for each of the three completives.

1. Statement: Makes a statement about an event viewed as complete.

| Mun sha shayi. Yara sun tuna malaminsu. |

‘We drank tea.’ ‘The children [they] remember their teacher.’ |

2. Question: Asks a question to which the answer could be “yes” or “no” about an event viewed as complete.

| Kun sha shayi? Yara sun tuna malaminsu? |

‘Did you drink tea?’ ‘Do the children [they] remember their teacher?’ |

3. Performative: Expresses the action of a “performative” verb (a verb with which one performs the action by uttering the verb itself, e.g. “I apologize!”, “I pronounce you man and wife!”).

| Mun gode Allah! Na k’i! |

‘We thank Allah!’ I refuse! |

4. With sai ‘until’: Expresses the completion of the event after an elapse of time.

| Sai na zo kallonsu. Sai an juma. |

‘[We’ll meet again] when I come to see them.’ “See you later.”, i.e. ‘[We’ll meet again] when one has passed time.’ (the verb juma mean ‘pass time’) |

1. Question word: Used in a question about a completed event when a question word (‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, etc.) is at the beginning of the sentence.

| Me suka sha? Wa ya sha shayin? Wane ne sukatuna? |

‘What did they drink?’ ‘Who [he] drank the tea?’ ‘Who do they remember?’ |

2. Emphasis: Makes a statement about a completed event when a word is put at the beginning of the sentence to emphasize it. (ne or ce ‘it is…’ sometimes appears after the emphasized word)

| Shayi suka sha. Bashir ne ya sha shayin. Malaminsu sukatuna. |

‘It is tea that they drank.’ ‘It is Bashir who [he] drank the tea.’ ‘It’s their teacher who theyremember.’ |

3. Relative clause: Used in any relative clause which refers to a completed event.

| shayin da suka sha mutumin da ya sha shayin. malamin da suka tuna |

‘the tea that they drank’ ‘the man who [he] drank the tea’ ‘the teacher whom theyremember’ |

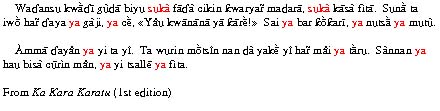

4. Narrative: Used in narratives about events in the past or viewed as being the the past, e.g. a tale, a news story, a historical account. The Relative Completive is used for the events that happen sequentially and carry the story to its next stage.

‘A certain two frogs [they] fell into a calabash of milk and they failed to get out. They were swimming away until one [he] got tired, and he said, “Today my days are finished!” Then he quit trying, he went under, and he died.

‘But the other one [he] kept at it. Through the movements that he was doing, butter [it] eventually formed. Then he climbed on the ball of butter, he made a jump, and he got out.’

Negative: Used in all contexts to show that an event has not been completed or a state realized. (There is no “plain/relative” distinction in the negative.)

| Ba su sha shayi ba. Ba ku sha shayi ba? Ban sani ba. Ba su tuna malaminsu ba. Wa bai sha shayi ba? shayin da ba su sha ba |

‘They didn’t drink tea.’ ‘Didn’t you drink tea?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘They don’t remember their teacher.’ ‘Who didn’t [he] drink tea?’ ‘the tea that they didn’t drank’ |

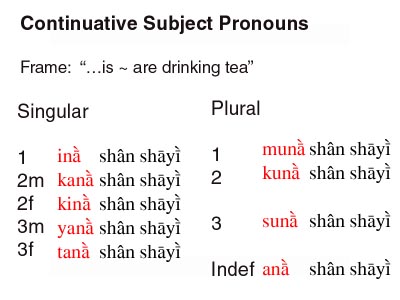

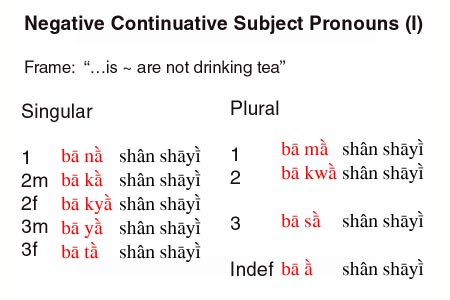

Continuative

Basic Meaning of the Continuative in Action

Hausa has three “Continuative” forms, but they share the same basic range of meaning:

- The Continuative indicates that an action extends over a period of time. This can mean that the action is ongoing or that the action is recurrent or habitual.

- English translation in the sense of ongoing action will usually be progressive, e.g. suna salla ‘they are praying’.

- English translation in the sense of habitual action will usually be simple present, e.g. suna salla ‘they pray’ (that is, ‘they pray on a regular basis, they are practicing Muslims’).

The table below illustrates the three Continuative forms, with translations in the “ongoing” sense. Click the highlighted links to see full pronoun paradigms.

| Continuative | Suna shan shayi. | ‘They are drinking tea.’ |

| Relative Continuative | Shayi suke sha. | ‘It is tea that they are drinking.’ |

| Negative Continuative | Ba sa shan shayi. | ‘They are not drinking tea.’ |

Active vs. stative verbs: Because the continuative represents ongoing action, it’s primary role is with active verbs. However, a few stative verbs normally use the continuative rather than the completive (the normal tense for stative verbs). Some important stative verbs normally using the continuative are:

| so | ‘want, like’ | Ina son shayi. Me kake so ka sha? |

‘I like tea.’ ‘What do you want to drink?’ |

| ji | ‘feel; hear, understand’ | Ba na jin dad’i. Kana jin Hausa? |

‘I don’t feel good.’ ‘Do you understand Hausa?’ |

ji can take the Completive as an alternative to the Continuative in the meaning ‘hear, understand’ at the present time, e.g. na ji jawabinka ‘I understand your point’.

Forms of Continuative

As with all Hausa tenses, the primary marker of tense is the form of the subject pronoun rather than the form of the verb. Hausa has three Continuative forms, whose functions are explained immediately below. The bases for forming the Continuative pronouns are as follows. Click on the highlighted links to see the full paradigms.

| Continuative | Relative Continuative | Negative Continuative |

| short, Hi pronoun + na | short, Hi pronoun + ke | long, Hi ba + long, low pronoun |

Uses of the three Continuative forms in action constructions

The three continuative forms share the basic meaning described above. The differences have to do with the contexts in which you wish to express that meaning. Below are lists of the main uses for each of the three continuatives.

1. Statement: Makes a statement about an event viewed as extending over a period of time.

| Muna shan shayi. Jakuna suna cin ciyawa. |

‘We are drinking tea.’ ‘The donkeys [they] are eating grass.’ |

2. Question: Asks a question to which the answer could be “yes” or “no” about an event extending over a period of time.

| Kuna shan shayi? Jakuna suna cin ciyawa.? |

‘Are you drinking tea?’ ‘Are the donkeys [they] eating grass?’ |

1. Question word: Used in a question about an ongoing event when a question word (‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, etc.) is at the beginning of the sentence.

1. Question word: Used in a question about an ongoing event when a question word (‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, etc.) is at the beginning of the sentence.

| Wa yake shan shayi? Me suke sha? Me jakuna sukeci? |

‘Who is [he] drinking tea?’ ‘What are they drinking?’ ‘What are the donkeys [they] eating?’ |

2. Emphasis: Makes a statement about an ongoing event when a word is put at the beginning of the sentence to emphasize it. (ne or ce ‘it is…’ sometimes appears after the emphasized word)

| Bashir ne yake shan shayi. Shayi ne suke sha. Ciyawa suke ci. |

‘It is Bashir who [he] is drinking tea.’ ‘It’s tea that they are drinking.’ ‘It is grass that they are eating.’ |

3. Relative clause: Used in any relative clause which refers to an ongoing event.

| shayin da yake sha ciyawar da jakuna suke ci |

‘the tea that he is drinking’ ‘the grass that the donkeys [they] are eating’ |

Negative Continuative

Negative: Used in all contexts to show that an event is not ongoing or does not happen on a regular basis.

| Tanko ba ya shan shayi. Ba sa shan shayi. Jakuna ba sa cin nama. Ba a bi ta gaban mai salla. Wa ba ya shan shayi. ciyawar da jakuna ba sa ci |

‘Tanko [he] isn’t drinking tea.’ ‘They are not drinking tea.’ ‘Donkeys [they] don’t eat meat.’ ‘One doesn’t pass in front of one who is praying.’ ‘Who isn’t [he] drinking tea?’ ‘the grass that the donkeys [they] are not eating’ |

Verb Form in the Continuative: Verbal Nouns

The continuative is the only Hausa tense which requires a special verb form. The continuative uses the verbal noun rather than the basic verb. We have a brief summary here. Click on the verbal nouns link just above for more details.

Two types of verbal nouns

- -wa verbal nouns add an ending –wa to the verb.

- Non-wa verbal nouns do not add a –wa ending. Rather, the verb may change its final vowel and/or its tones. Unfortunately, there is no way to predict from the verb itself what the form of its non-wa verbal noun will be.

Some verbs have only –wa verbal nouns, some have only non-wa verbal nouns, some have both. Here are a few verbs in the Completive (illustrating the base form of the verb) and the Continuative (illustrating the verbal noun).

| Completive (base verb) | Continuative (verbal noun) | |

| -wa verbal nouns | Sun huta. ‘They rested.’Sun fito. ‘They came out.’Sun taru. ‘They gathered.’ |

Suna hutawa. ‘They are resting.’Suna fitowa. ‘They are coming out.’Suna taruwa. ‘They are gathering.’ |

| Non-wa verbal nouns | Sun tashi. ‘They got up.’ (verb ends in a short vowel)Sun saya. ‘They bought.’Sun taimaka. ‘They helped.’Sun nema. ‘They looked.’ (verb has Low-High tones)Sun tafi. ‘They went.’ |

Suna tashi. ‘They are getting up.’ (verbal noun ends in a long vowel)Suna saye. ‘They are buying.’Suna taimako. ‘They are helping.’Suna nema. ‘They are looking.’ (verbal noun has High-High tones)Suna tafiya. ‘They are going.’ |

Objects in the Continuative

- -wa verbal nouns drop the -wa when an object follows. Thus, a verb in the Continuative with an object looks just as it would in any other tense.

- Non-wa verbal nouns require the genitive linker before a noun object and the possessive pronouns as pronoun objects.

| Completive (base verb) | Continuative (verbal noun) | |

| -wa verbal nouns | Sun zuba sukari. ‘They poured sugar .’Sun kawo kaza. ‘They brought a hen.’Sun kama ni. ‘They caught me.’Na raba su. ‘I separated them.’Sun goge mota. ‘They polished the car.’ |

Suna zuba sukari. ‘They are pouring sugar.’Suna kawo kaza. ‘They are bringing a hen.’Suna kama ni. ‘They are catching me.’Ina raba su. ‘I am separating them.’Suna goge mota. ‘They are polishing the car.’ |

| Non-wa verbal nouns | Sun sami izini. ‘They got permission.’Sun sayi kabewa. ‘They bought a pumpkin.’Sun taimake ni. ‘They helped me.’Sun neme ka. ‘They looked for you.’Sun ci doya. ‘They ate yam.’ |

Suna samun izini. ‘They got up.’Suna sayen kabewa. ‘They are buying a pumpkin.’Suna taimakona. ‘They help me.’Suna nemanka. ‘They are looking for you.’Suna cin doya. ‘They are eating yam.’ |

Indirect Objects in the Continuative

- -wa verbal nouns drop the -wa before indirect objects just as they do before direct objects. Thus, a verb in the Continuative with an indirect object looks just as it would in any other tense.

- Non-wa verbal nouns cannot be used with indirect objects. Rather, verbs that require non-wa verbal nouns take special indirect oject forms. With such verbs, the verb form in the continuative with indirect objects is therefore identical to the verb form in other tenses. This situation most often arises with Variable Vowel Verbs, all of which use non-wa verbal nouns. See comments on Variable Vowel Verbs before indirect objects for comments on the forms used with indirect objects.

| Completive (base verb) | Continuative (verbal noun) | |

| -wa verbal nouns | Sun kawo mini kaza. ‘They brought me a hen.’Na raba wa bak’i goro. ‘I distributed kolas to the guests.’Sun goge masa mota. ‘They polished the car for him.’ |

Suna kawo mini kaza. ‘They are bringing me a hen.’Ina raba wa bak’i goro. ‘I am distributing kolas to the guests.’Suna goge masa mota. ‘They are polishing the car for him.’ |

| Non-wa verbal nouns | Sun saya wa matansu kabewa. ‘They bought pumpkin for their wives.’Sun nemam mini shi. ‘They sought him for me.’ |

Suna saya wa matansu kabewa. ‘They buying pumpkins for their wives.’Suna nemam mini shi. ‘They are seeking him for me.’ |

The Continuative with Action Nouns

A verb in the continuative is in the verbal noun form. In fact, the continuative can be used with any noun which represents an action, whether or not there is a verb associated with it. Here is a list of some common action nouns which have no associated verb (or at least no verb in common use):

| aiki bacci dariya fad’a fama fata hira kuka magana murmushi rawa salla wak’a wasa |

‘working’ ‘sleeping’ ‘laughing’ ‘fighting” ‘struggling’ ‘hoping’ ‘chatting, conversing’ ‘crying’ ‘talking, speaking’ ‘smiling’ ‘dancing’ ‘praying’ ‘singing’ ‘playing’ |

In tenses other than the continuative, the only way to express these notions as actions is to use the verb yi ‘do’, saying ‘he did work(ing)’, etc. In the continuative you can use yi in its verbal noun form, with a falling tone, in which case the genitive linker -n is required before the action noun (as with verbal nouns + a noun object). However, yi is often omitted in the continuative.

| Completive (must use yi) | ||

|

||

| Continuative (yi is optional) | ||

|

Omission of Pronouns in the Continuative

When a subject is present before the verb, the pronoun part of the continuative pronouns (ya ‘he’, ta ‘she’, su ‘they’, etc.) can be omitted, leaving just the –na of the plain continuative pronouns or the –ke of the relative continuative pronouns.

| Bala yana shan shayi. = Bala na shan shayi. Zainab tana shan shayi. = Zainab na shan shayi. Mutane suna shan shayi. = Mutane na shan shayi. |

‘Bala is drinking tea.’ ‘Zainab is drinking tea.’ ‘The people are drinking tea.’ |

| Wa yake shan shayi? = Wa ke shan shayi? Me Bala yake sha? = Me Bale ke sha? Ita ce take shan shayi. = Ita ce ke shan shayi. mutanen da suke shan shayi = mutanen da ke shan shayi |

‘Who is drinking tea?’ ‘What is Bala drinking?’ ‘SHE is drinking tea.’ ‘the people who are drinking tea’ |

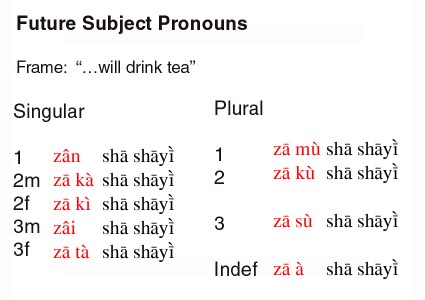

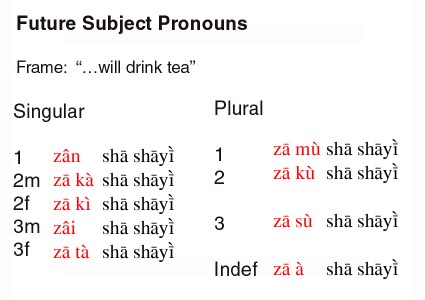

Future

Basic Meaning of the Future

Hausa Future has the following meaning:

- The Future indicates that the event expressed by the verb will begin at a time later than the time of reference:

- If the time of reference is the moment of speaking (the present), the English translation will be will or gonna, e.g. zan sha shayi ‘I will drink tea, I’m gonna drink tea.’

- If the time of reference is some time in the past, the English translation will be was going to or was about to, e.g. da zan sha shayi ‘earlier I was going to drink tea, earlier I was about to drink tea.’

Form of the Future

As with all Hausa tenses, the Future tense is marked by the form of the subject pronoun rather than by the form of the verb. Click on the highlighted link to see the full paradigm.

Future: Long, Hi za precedes the pronoun. In the first person singular, za contracts with the pronoun to give zan, and in third person masculine singular za contracts with the pronoun to give zai. If there is a noun subject, it precedes the za.

| Za su zo. Zan sha shayi. Bala zai ba abokinsa goro. |

‘They will come.’ ‘I will drink tea.’ ‘Bala [he] will give his friend kolas.’ |

Negative Future

Negative future: Short, Lo ba before the za of the future and a second short, Hi ba at the end of the sentence.

| Ba za su zo ba. Ba zan sha shayi ba. Bala ba zai ba abokinsa goro ba. |

‘They will not come.’ ‘I will not drink tea.’ ‘Bala will not give his friend a kola.’ |

Use of the Future

The Future can be used in essentially any context calling for future meaning. As noted above under Basic meaning of the Future, the Future can refer to past time in the meaning that an event “was going to” take place or “was about to” take place.

Present Context

| Za su tafi Amirka bad’i. | ‘They will travel to America next year.’ |

| An gina matattarar ruwa kamar yadda za ku gani. | ‘They have built a reservoir as you will see.’ |

| Ina zaton za su kai ni k’arshen wata. | ‘I think they will take me to the end of the month.’ |

Past Context

| Mutane za su yi musu bai kwana ba, sai malaman nan hud’u suka shaida ya kwana.

from Magana Jari Ce, 1 vol. edition, p. 155) |

‘The people were about todispute that he had not spent the night (there), when those four learned men bore witness that he had spent the night.’ |

| Sai ya juya kamar zai tafi. | ‘Then he turned as if he were gonna leave.’ |

| Ba ni zaton zai bugi yarinyan nan haka. | ‘I didn’t think he would beat that girl like that.’ |

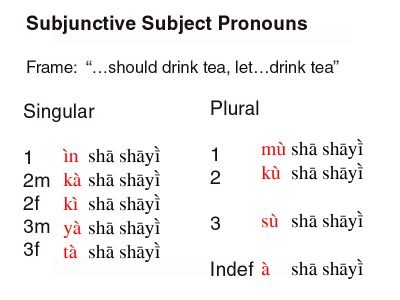

Subjunctive

It is difficult to provide a simple, unified “meaning” for the Subjunctive because, by definition, the meaning of the Subjunctive often is dependent on the construction that it is used in (subjunctive comes from Latin “joined under”, i.e. “dependent”). Nonetheless, we can provide a rough characterization as follows:

- The Subjunctive indicates that the event expressed by the verb will begin at a time later than the time of speaking or than the time of the construction to which it is dependent. For example,

- Later than the time of speaking: Subjunctive canbe used to give a command or exhortation, e.g. ku zo mu tafi! ‘[you] come on and let’s go!’ [The commanded event takes place later than the command itself.]

- Later than the time of a construction to which it is dependent, e.g.

- After so ‘want’: Ina so ya zo ‘I want him to come’ [The “wanting” precedes the event that is wanted.]

- With dole ‘it is necessary: Dole ya zo ‘it is necessary that he come’ [The necessity precedes the necessary event.]

- Purpose: na kira shi domin ya zo ‘I called him so that he (would) come’ [The calling precedes the event that will result because of the calling.]

Form of the Subjunctive

As with all Hausa tenses, the Subjunctive is marked by the form of the subject pronoun rather than by the form of the verb. Click on the highlighted link to see the full paradigm.

Subjunctive: Short, Low tone pronouns in all persons

| Ku zo! Yana so in sha shayi. Ya kamata Bala ya ba abokinsa goro. |

‘Come!’ [plural imperative]

‘He wants me to drink tea.’ ‘It is fitting that Bala [he] give his friend kolas.’ = ‘Bala [he] should give his friend kolas.’ |

Negative Subjunctive

Negative Subjunctive is the only negative form in Hausa which does not use ba somewhere in the sentence. To express Negative Subjunctive,

- Place kada before the Subjunctive expression.

- Kada often contracts to kar, which, in turn is usually pronounced kaC, were C = the next consonant in the sentence after kada.

- Kada mu tafi! –> Kar mu tafi! –> Kam mu tafi! ‘Let us not go!’

- Kada ki tsaya! –> Kar ki tsaya! –> Kak ki tsaya! ‘Don’t stop!’

- Kada su fita! –> Kar su fita! –> Kas su fita! ‘They shouldn’t go out!’

- If the subject is a noun, kada precedes it.

- Kada yara su fita! (–> Kar yara su fita!’ –> Kay yara su fita!) ‘The children shouldn’t go out!’

| Kada ku zo! Kada ki sha shayi! Kada ka sha shayi! Ya b’uya don kada in gan shi. Kada Bala ya ba abokinsa goro. |

‘Don’t come!’ [negative plural imperative]

‘Don’t drink tea!’ [negative fem. imperative]

‘Don’t drink tea!’ [negative masc. imperative]

‘He hid so that I wouldn’t see him.’ ‘Bala [he] shouldn’t give his friend kola.’ |

The Negative Subjunctive is the form Hausa uses to express Negative Imperative in both singular and plural.

Some functions of the Subjunctive

We can break down the uses of the Subjunctive into several categories. Though the range of uses is large, they essentially all share the property of indicating an event which will take place as a result of a command, a wish, a purpose, fittingness to the situation, or the beginning of a non-completed series of events.

- Imperative: The Subjunctive is an alternative to the Imperative for commands to a single person and is the only available form for commands to a group and negative commands. (See a comment on using Imperative or Subjunctive for commands.)

| Ki tsaya! (= Imperative tsaya!) Ka tsaya! (= Imperative tsaya!) Ku tsaya! |

‘Stop!’ (to a female) ‘Stop!’ (to a male) ‘Stop!’ (to a group) |

| Kada ki tsaya! Kada ka tsaya! Kada ku tsaya! |

‘Don’t stop!’ (to a female) ‘Don’t stop!’ (to a male) ‘Don’t stop!’ (to a group) |

- Exhortations other than 2nd person: The Subjunctive expresses exhortations to 1st person and 3rd person. In 1st person, the English translation will usually begin let me or let’s, and in Hausa, more often than not, such exhortations begin with bari, which is the Imperative form of ‘leave, let’. In third person, a frequent use is invocations of Allah.

| Bari in tsaya! Mu tsaya!, Bari mu tsaya! |

‘Let me stop!’ ‘Let’s stop!’ |

| Ya tsaya! Su shigo. Allah ya kiyaye hanya! Allah ya ba mu alheri! |

‘He should stop!’ ‘Have them come in.’ ‘May Allah protect (you on your) journey!’ ‘May Allah give us good fortune!’ |

- Reported commands and exhortations

| Me suka ce da kai ka yi? Na umurce shi ya zauna. |

‘What did they tell you to do?’ ‘I ordered him to sit down.’ |

- Purpose: In this use, the conjunctions domin/don/saboda ‘in order that’ may introduce the Subjunctive clause.

| Ta tafi kasuwa (don) ta yiwo cefane. | ‘She went to the market to do shopping.’ |

- Expressions of necessity, appropriateness, fittingness, and the like: Some of the more frequent expressions in the category are ya kamata ‘it is fitting’ (often translatable as “should”), dole or tilas ‘it is necessary’, and gara ‘it would be better’.

| Ya kamata su tuba. Dole ka biya haraji. Gara ta hak’ura. |

‘They should repent.’ ‘You have to pay taxes.’ ‘It would be best for her to be patient.’ |

- Expressions of desire, admonition, and the like: By far the most frequent expression in this category is so ‘want, like’.

| Ina so su fad’i gaskiya. Tana so ta sami miji mai kud’i. |

‘I want them to tell the truth.’ ‘She want to get a husband with money.’ |

- Expressions of intention, attempt, possibility: Some expressions in this category are yi k’ok’ari ‘try’ and ya yiwu ‘it is possible’.

| Sai ka yi k’ok’ari ka biya shi. Ya yiwu a same shi. |

‘You should try to pay him.’ ‘It’s possible that one will find it.’ |

- With sa ’cause’, bari ‘allow’ in non-completive context:

| Me zai sa ya fad’i haka? Yana barinmu mu yi. |

‘What would cause him to talk like that?’ ‘He lets us do it.’ |

- With kafin ‘before’, maimakon ‘instead of’, balle/bare ‘much less’:

| Kafin ka dawo, yaranka duk sun girma. | ‘Before you come back, your children will have all grown up.’ |

| Audu ya ci k’osai maimakon yaci waina. | ‘Audu ate bean cakes instead of eating millet cakes.’ |

| Ya yi tafiya ba hutu balle ya ci abinci. | ‘He traveled without a rest much less did he eat food.’ |

- Clauses in sequence to an Imperative, other Subjunctives, Future, “Indefinite” Future, Habitual, and Continuative: In English when several actions occur as a group, we can simply join the verbs with commas or ‘and’, e.g. ‘They will enter, sit down, and drink water.’ In Hausa every verb must be accompanied by a subject pronoun marking tense. In verb groups using the underlined tenses here, only the first verb shows that tense marking, and all subsequent verbs in the same group use the Subjunctive.

| after Imperative | Shiga ka zauna ka sha ruwa. | ‘Enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

| Subjunctive | Ya kamata su shiga su zauna susha ruwa. | ‘They should enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

| Future | Za su shiga su zauna su sha ruwa. | ‘They will enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

| “Indef” Future | Saa shiga su zauna su sha ruwa. | ‘They will surely enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

| Habitual | Sukan shiga su zauna su sha ruwa. | ‘They enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

| Continuative | Suna shiga su zauna su sha ruwa. | ‘They enter, sit down, and drink water.’ |

Non-past narrative (“procedural discourse”): This type of narrative usually combines idan ‘when’ clauses with Subjunctive clauses. The Subjunctive clauses sometimes begin with sai ‘then’.

A zuba rairayi a cikin tukunya, a soya ya yi zafi sosai. Idanrairayin ya yi zafi, sai a zuba masara a ciki, a ci gaba da juyawa da cokalin katako ko mara har sai ta dafu ta fara yin ja.

‘One pours sand in a pot, [one] heats (it), (and) itgets very hot. When the sand has gotten very hot, then one pours the corn in and [one] continues stirring with a wooden spoon or scoop until it is cooked through and it starts turning red.’

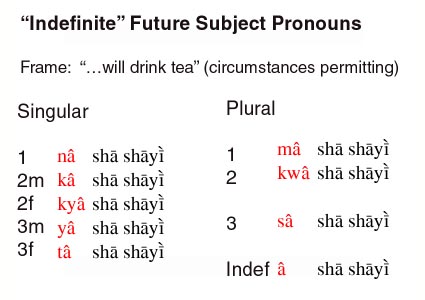

“Indefinite” Future

Basic Meaning of the “Indefinite” Future

Like the Future, the “Indefinite” Future refers to an event which has not yet begun at the moment of speaking. It is sometimes interchangeable with the Future. However, the “Indefinite” Future has an element of meaning different from the Future and differs from it in other ways as well.

- The “Indefinite” Future, like the Future, indicates that the event expressed by the verb will take place at a time later than the moment of speaking but unlike the Future, there is an element of “conditionality” or diffidence attached to it, which one might characterize as an unexpressed “if circumstances permit” or “Lord willing”.

- In English translation, ironically, addition of “surely” will often give the sense of the “Indefinite” Future, e.g. sa zo ‘they will surely come’. Note that “surely” in English suggests the opposite of certainty, i.e. the speaker is conveying some diffidence in predicting that they will come.

In addition to the meaning of diffidence or conditionally conveyed by the “Indefinite” Future, but not the Future, there are differences in usage between the two.

- Questions, emphasis, relative clauses: The Future, but NOT the “Indefinite” Future can appear in questions beginning with a question word, sentences with a word placed at the beginning for emphasis, and relative clauses.

| Future: Me za ku saya? NOT “Indefinite” F.: *Me kwaasaya? |

‘What will you buy?’ |

| Future: Wake za mu saya. NOT “Indefinite” F.: *Wake maasaya. |

‘Beans is what we will buy.’ |

| Future: waken da za mu saya NOT “Indefinite” F.: *waken da maa saya |

‘the beans that we will buy’ |

- Future in the past: The Future can be used in contexts referring to events in the past, where is it usually translated ‘was going to’ or ‘was about to’. The “Indefinite” Future cannot be used this way, i.e. the “Indefinite” Future always refers to events that would be in the future with reference to the time of speaking.

| Future: Da za mu sha shayi. NOT “Indefinite” F.: *Da maa sha shayi. |

‘Earlier we were going todrink tea.’ |

- Future in clauses introduced by ‘if’ or ‘because’: The Future, but not the “Indefinite” Future can appear in clauses stating conditions or reasons.

| Future: In za ka huta, ka huta a babbar inuwa. NOT “Indefinite” F.: *In kaa huta, … |

‘If you’re gonna rest, rest in full shade.’ |

| Future: Da za su samu, sai su karb’a. NOT “Indefinite” F.: *Da saa samu, … |

‘Were they gonna get (it), they should accept it.’ |

| Future: Tana zuwa wurin likita don za ta haifu. NOT “Indefinite” F.: *…don taa haifu. |

‘She is going to the doctor because she’s gonna give birth.’ |

Technical Remarks on Differences in Usage Between Future and “Indefinite” Future

The differences in usage between the Future and “Indefinite” Future follow from the meaning difference between the two forms, i.e. the element of diffidence or uncertainty inherent in the “Indefinite” Future but not the Future.

- Question, emphasis, relative clauses: The Future, but not the “Indefinite” Future can appear in these contexts. These three situations all involve what is called a presupposition. If I ask, “What will you buy?”, I presuppose that you are going to buy something. If I say, “What we will buy is beans,” there is a presupposition that we we will buy things, and I am stressing what they will be. If I say, “the beans that we will buy,” I presuppose that there are some beans that I can describe by saying that they are the ones that we will buy. Clearly, if I presuppose that an event will take place, I cannot be diffident or hesitant about saying that it will take place. Hence, the “Indefinite” Future would be inappropriate in such contexts.

- Future in the past: The Future can be used in contexts referring to events in the past, where is it usually translated ‘was going to’ or ‘was about to’. If the context for such events is past time, I know what the situation was, i.e. I would not be diffident or hesitant in making a statement about what was being planned, even if it turned out not to take place. Hence, the “Indefinite” Future would be inappropriate.

- Future in clauses expressing conditions or reasons: If I say, “If you are going to rest, rest in full shade,” I am not diffident about the event in the conditional clause–this is a given for the outcome in the main clause (which I may or may not be diffident about). Likewise, if I say, “She will go to the doctor because she’s gonna give birth,” I am using the “reason” (‘because’) clause as a given in order to explain the event in the main clause (which I may or may not be diffident about). Since in both conditional and reason clauses, the event is a given with relation to what happens in in the main clause, the “Indefinite” Future would not be appropriate.

These usage differences between the two futures are not something which might be called part of the grammar of Hausa, in contrast to the superficially similar differences in usage between the Completive and Relative Completive and the Continuative and Relative Continuative. Thus, for example, in a pair of sentences like

| Continuative: Suna sayen kabewa. | ‘They are buying pumpkin.’ |

| Relative Cont.: Me suke saye? | ‘What are they buying?’ |

there is no difference in the meaning of the Continuative, per se, in the two sentences–both refer to an ongoing event. It is simply a grammatical fact of Hausa that the statement uses the “plain” Continuative, the question uses the Relative Continuative.

In the case of the two futures, if you have a correct concept of the meaning of the “Indefinite” Future, you would know that it would not fit the meaning of the sentence to use the “Indefinite” Future in a context involving presupposition, past time, or an event set forth as a “given”.

Form of the “Indefinite” Future

As with all Hausa tenses, the “Indefinite” Future is marked by the form of the subject pronoun rather than by the form of the verb. Click on the highlighted link to see the full paradigm.

“Indefinite” Future: Pronouns with long –a and Falling tone.

| Saa zo. Naa sha shayi. Bala yaa ba abokinsa goro. |

‘They will surely come.’ ‘I will most likely drink tea.’ ‘Bala [he] will undoubtedly give his friend kolas.’ |

Negative “Indefinite” Future

Negative “Indefinite” Future: Short, Lo ba before the pronoun marking the “Indefinite” Future and a second short, Hi ba at the end of the sentence.

| Ba saa zo ba. Ba maa sha giya ba. Bala ba yaa ba abokinsa goro ba. |

‘They most likely will not come.’ ‘We will surely not drink alcohol.’ ‘Bala will most likely not give his friend a kola.’ |

Examples of Usage of the “Indefinite” Future

One can use the “Indefinite” Future in most contexts where one is expressing diffidence about whether an event will take place. It is particularly common (1) when one is making a mild promise and (2) following conditional clauses or other types of clauses which set up a situation where something is a reasonably predictable outcome. The latter usage is common in proverbs, of which those below are typical.

Mild Promises

(A common leave-taking formula.)

| A: Ki gai da gida. B: Gida yaa ji. |

A: ‘Greet those at home.’ B: Those at home will surely hear (your greeting).’ |

| Mun ji abin da ka ce, maako bi. | ‘We have heard what you have said, (and) we will indeed follow through.’ |

Following Clauses that Set up Conditions

- Kome ka hak’ura da shi, kaa ga bayansa.’

- Anything you are patient with, you will see its end.’

- In kunne ya ji muguwar magana, wuya yaa tsere.’

- If the ear hears inauspicious talk, the neck [it] will escape.’

- In da duniya tana da gaskiya, ba aa bar mazari tsirara ba.’

- If the world had justice, one would surely not leave the spinner (of cotton thread) naked.’

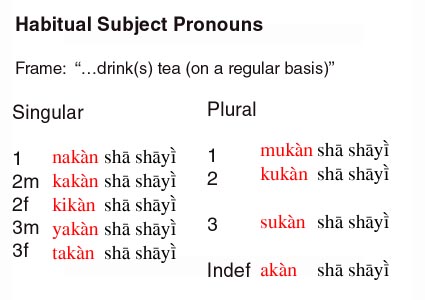

Habitual

Basic Meaning of the Habitual

The name of the Habitual is self-descriptive.

- The Habitual, indicates that the event expressed by the verb takes place on a regular basis or at regular intervals.

- If the Habitual event applies to the present time, the English translation is usually just the simple present, e.g. sukan zo da safe ‘they come in the morning, they come mornings.’

- If the Habitual event applies to a period in the past, the English translation is usually used to or would, e.g. da sukan zo da safe ‘formerly they used to come in the morning, they would come in the morning.’

Form of the Habitual

As with all Hausa tenses, the Habitual is marked by the form of the subject pronoun rather than by the form of the verb. Click on the highlighted link to see the full paradigm.

Habitual: High tone, short pronouns + Low tone kan.

| Sukan zo. Nakan sha shayi (da safe). Bala yakan ba abokansa goro. |

‘They (always) come.’ ‘I drink tea (in the morning).’ ‘Bala generally gives his friends kolas.’ |

Negative Habitual

Negative Habitual: The Habitual form is not used in the negative. To express the concept of habitually not doing an activity, Hausa uses the Negative Continuative. Compare the following proverb with the proverbs below, which have the affirmative Habitual.

- In Fulani na kusa, ba a fad’in tsadan nono. [Negative Continuative ba a]

- ‘If Fulani are nearby, one doesn’t talk about the high price of milk.’

Use of the Habitual

The Habitual is the least frequently occurring of the Hausa tense forms. Some dialects do not use the Habitual form, rather using the Continuative to express the concept of occurrence on a regular basis. Even in the Kano dialect, where the Habitual is in regular use, speakers often use the Continuative where a Habitual form might also be appropriate.

To illustrate the Habitual, here are some proverbs which use it:

- Inda yaro ya tsinci wuri, nan yakan fi saurin tunawa.

- ‘Where a child finds a cowrie, there he is most quick at remembering.’

- An san biri yana da wuya, akan d’aure shi a gindi.

- ‘One knows that a monkey has a neck, (but) one ties him at the waist.’

- Mai k’afa hud’u yakan fad’i bare mai biyu.

- ‘Someone with four feet [he] falls, how much less someone with two.’

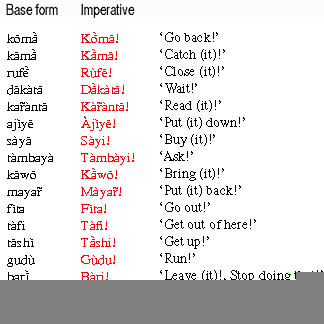

Imperative

Basic Meaning of the Imperative

The Imperative has a similar function to the Imperative of European languages, though in Hausa a special Imperative verb form is limited to giving affirmative commands to singular subjects.

The Imperative is used to issue an affirmative command to one person, e.g. zo! ‘come!’

Form of the Imperative

The Imperative takes no subject pronoun and uses a special tonal pattern.

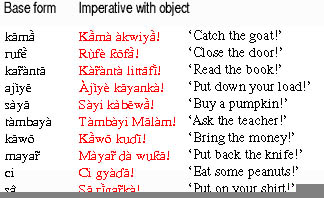

- Basic Imperative form: The verb has a Low…High tone pattern (all syllables but the last syllable are Low) regardless of base form. Note that monosyllabic verbs have only a “last” syllable and hence bear High tone.

Imperatives have a number of special features in addition to the basic Low-High tone pattern.

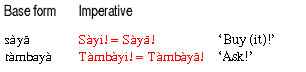

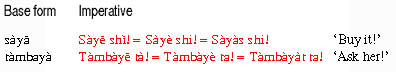

- Variable Vowel Verbs: Variable Vowel Verbs with no object following end in –i in the Imperative (see Sayi! and Tambayi! in the list above).

- Tones with noun objects: Most verbs have the Lo…Hi Imperative pattern with noun objects. However, “regular verbs” ending in -a or -e have all Low tones and a final short vowel. (See technical note on verbs with final -e.)

- Tones with pronoun objects: Monosyllabic verbs take Low tone before pronoun objects. One can think of the Verb + pronoun object as comprising the Low-High Imperative tone pattern. Note that the pronoun tone of the first four verbs is High, even though the verb ends in High.

Technical Remarks on Imperatives with Variable Vowel Verbs

Variable Vowel Verbs show some speaker and dialectal variation in the Imperative. The description in the online grammar presents a common pattern in Kano Hausa, but even within Kano, speakers vary. The main variations are as follows:

- No object following the verb: Some speakers have a final –i on Imperatives of Variable Vowel Verbs with no following object, others have final –a, the “no-object” form of other tenses.

- Pronoun object following the verb: Some speakers use an Imperative with a Low-High pattern and final long –e before pronoun objects, just as Variable Vowel Verbs in other tenses. Others use a Low-Low pattern and short –e (with High tone on the pronoun, which is, as expected, opposite in tone to the preceding syllable). Yet others use a Low-Low pattern with final –aC where “C” is a doubling of the next consonant.

The final –i of Variable Vowel Verbs with no following object in the Imperative is a remnant from a time when all Imperatives changed their vowel in the Imperative. The languages most closely related to Hausa in the Chadic family, such as Bole, Karekare, Bade, or Ngizim, spoken to the east of Hausa still form their imperatives this way. The imperative form of bari ‘leave’ also bears this remnant Chadic Imperative –i. We can tell this because the base form of the verb ends in long -i, but the imperative ends in short –i. Moreover, some speakers retain the -i of the imperative even before objects whereas the –i of the base form drops before objects.

Negative Imperative

The Imperative form is not used in the negative. Negative Imperative is expressed by the Negative Subjunctive.

| Kada ki dakata! Kada ka ci! Kada ki rufe k’ofa! Kada ka ajiye kayanka! Kada ki kama ta! Kada ka mayar da ita! |

‘Don’t wait!’ ‘Don’t eat (it)!’ ‘Don’t close the door!’ ‘Don’t put down your load!’ ‘Don’t catch her!’ ‘Don’t put it back!’ |

Use of the Imperative

The Imperative form can only be used only in affirmative commands directed to a single person (male or female). Commands directed to more than one person use the 2nd person plural Subjunctive, and negative commands use the Negative Subjunctive.

| Tsaya! Ku tsaya! |

‘Stop!’ (said to male or female) ‘Stop!’ (said to a group) |

| Kada ki tsaya! Kada ka tsaya! Kada ku tsaya! |

‘Don’t stop!’ (said to a female) ‘Don’t stop!’ (said to a male) ‘Don’t stop!’ (said to a group) |

Imperative and Subjunctive in commands: Either the Imperative or the Subjunctive can be used to give commands to a single person. Some grammars claim that the Imperative is an “abrupt” command and the Subjunctive is a “polite” command. This is incorrect! Neither form, in itself, carries a sense of “abruptness” or “politeness”, and one can hear either form used when a social subordinate speaks to a social superior and vice-versa. As in any society, Hausa speakers follow certain patterns of protocol when addressing others, but conveying politeness in commands would be through means other than a simple choice between Imperative or Subjunctive. See R.M. Newman & A.M. Gimba, Hausa a Dace: A Guide to Functional Hausa (Indiana University, African Languages Program, Institute for the Study of Nigerian Languages and Cultures, 1998) for linguistic interactions in a large variety of social contexts.

Special Imperative ‘go’ and ‘come’

Hausa has the following special forms for the commands ‘go (on/away)!’ and ‘come (here)!’:

| Je ki! Je ka! Je ku! Ya ki! Ya ka! (Ku zo! = Subjunctive–no special form for a group) |

‘Go on!’ (said to a female) ‘Go on!’ (said to a male) ‘Go on!’ (said to a group) ‘Come here!’ (said to a female) ‘Come here!’ (said to a male) ‘Come here!’ (said to a group) |