Hausa Verb Forms

Factors influencing the forms that verbs take

Unlike most European languages, differences in Hausa verbs do not usually relate to marking verb tense. However, Hausa has several verb classes that differ primarily in the forms that verbs take depending on their objects or lack of objects. The factors that affect the forms of verbs are the following:

- No object following: There may be no object present in the sentence at all, the object may be someplace other than after the verb, or the word following the verb may not be considered an “object” in Hausa.

| No object at all: | Ka saya? | ‘Did you buy (it)?’ (the object is understood, perhaps from the context) |

| Object not after verb: | Shinkafa na saya. | ‘It is rice that I bought. (‘rice’ is the object, but it is at the beginning of the sentence for emphasis) |

| Word after verb not an “object”: | Sun shiga gida. | ‘They entered the house.’ (with most verbs of motion, the goal of the motion is a “locative” rather than an object) |

- Noun object following: In Hausa, any object which is not one of the special direct object pronouns counts as a “noun” object.

| Na sayi akwiya. | ‘I bought a goat.’ |

| Ka sayi wannan? | ‘Did you buy this?’ (though wannan ‘this’ is a “pronoun”–it stands for a noun–it is not one of the special direct object pronouns) |

- Pronoun object following: In Hausa, “pronoun object” refers only to an object expressed as one of the special direct object pronouns.

| Na saye ta. | ‘I bought it.’ |

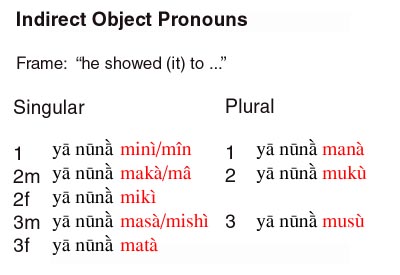

- Indirect object following: This may be either a pronoun indirect object or a noun indirect object (in Hausa, indirect object always come immediately after the verb).

| Na saya miki akwiya. | ‘I have bought a goat for you.’ |

| Na saya wa matata ita. | ‘I bought it for my wife.’ |

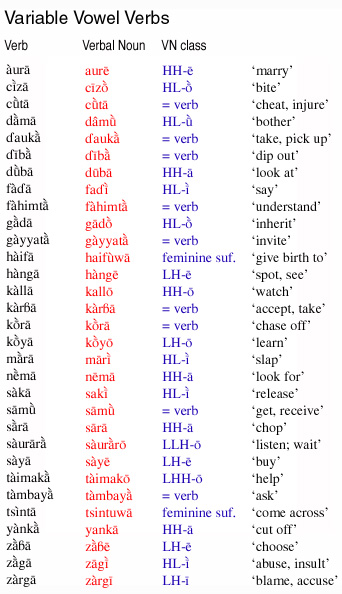

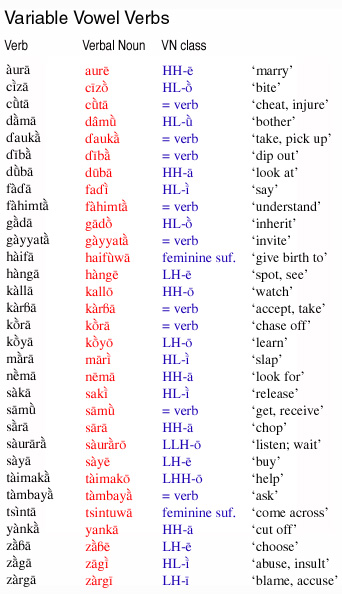

Variable Vowel Verbs

Variable Vowel Verbs (“VVV’s”), called Grade 2 in the Hausa Grade System, change their final vowel depending on the type of object which follows the verb. This is true for all verb tenses other than the Continuative (which uses the verbal noun rather than the base verb). The vowel variants of VVV’s are as follows:

No object or direct object following verb (see below for indirect object):

| No object following |

-a |

|

| Pronoun object following |

-e |

|

| Noun object following |

-i |

Tone–Note the following tonal features of VVV’s:

- All transitive verbs which begin in Low tone are Variable Vowel Verbs.

- All but 3-5 VVV’s begin in Low tone. In the Kano dialect, the VVV’s which do not begin in Low tone are d’auka ‘take’, d’iba ‘dip out’, and samu ‘get’. Even these verbs begin in Low tone when a pronoun or noun object follows. (See list of representative VVV’s with their tones marked.)

- Two-syllable VVV’s always have Low-High tones (see saya ‘buy’ in the examples above).

- Three-syllable VVV’s have Low-High-Low tones when no object follows and Low-Low-Highwhen there is an object (see tambaya ‘ask’ in the examples above). (Verbs with more than three syllables add additional Low tones at the beginning.)

Indirect objects with VVV’s

Before indirect objects, VVV’s take one of two patterns. One must simply learn which pattern applies to a particular verb. Some verbs can use either (as with tambaya ‘ask’ below).

Reversed tone pattern:

Hi-Lo(-Hi) instead of Lo-Hi(-Lo)

All High tones with final -ar (becomes -ambefore m)

For more information on Variable Vowel Verbs, see discussion of verbal nouns for Variable Vowel Verbs.

Regular Verbs other than Variable Vowel Verbs

By “regular” we mean verbs which follow predictable patterns of the majority of the basic verbs of Hausa. Here, we will consider only verbs which begin in High-Tone and end in -a or -e. (In the technical terminology of the Hausa Grade System, these are Grades 1 & 4.) These verbs have the following forms:

- Base form final vowel: Long -a or long -e.

- Base form tone: Two-syllable verbs have High-Low tones. Three-syllable verbs have High-Low-High tones. (Verbs of more than three syllables have additional High tone syllables at the beginning.) (See note on tone of pronoun objects.)

- Noun object following: The final vowel shortens for all verbs; three-syllable verbs have final Low tone. (See note on vowel length of final -e.)

- Everywhere else, regular verbs take their base form.

| No object following | |

| Pronoun object following | |

| Noun object following | |

| Indirect object following |

Minor Verb Classes and Irregular Verbs

By far the largest classes of underived verbs in Hausa are Variable Vowel Verbs and “regular” verbs ending in -a or -e. There are a few verbs in Hausa which do not follow the patterns of these verbs. We divide them into five groups here:

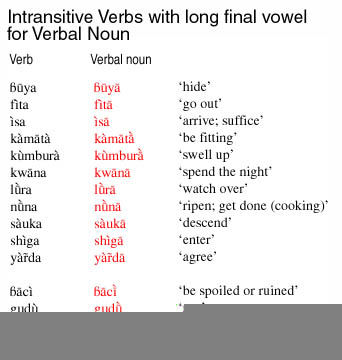

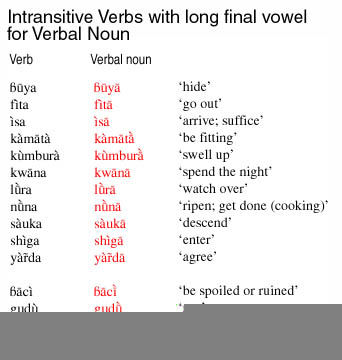

- Intransitive verbs: A number of intransitive verbs end in -i or -u. These final vowels not found with the common verb classes. A fairly large group of intransitives resemble Variable Vowel Verbs in that they end in -a and have Low-High tones, but unlike VVV’s, they have short final vowels. Some intransitive verbs also have High-High tones with final short -a. Since intransitive verbs, by definition, cannot take objects, they do not undergo the types of variations that transitive verbs can undergo.

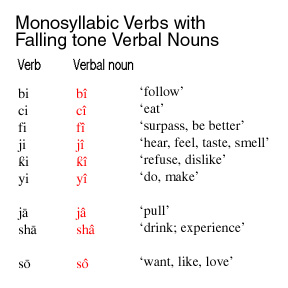

- Monosyllabic verbs: All but two monosyllabic verbs have High tone (the two exceptions are sa ‘put on; cause’ and ce ‘say’, which have falling tones and pattern with regular verbs in -aor -e). Monosyllabic verbs are invariant except that those that end in a short vowel lengthen their vowel before a pronoun direct object.

- The verbs biya ‘pay’ jira ‘wait for’, kira ‘call’, riga ‘precede’: These four verbs have High-High tones and long final -a everywhere. They are “irregular” in the sense that there are only four of them and they have unusual verbal nouns.

- The verbs bari ‘leave’, sani ‘know’, gani ‘see’: These three verbs drop the final -i before any object. Gani drops the final -ni before noun objects. (See above for forms)

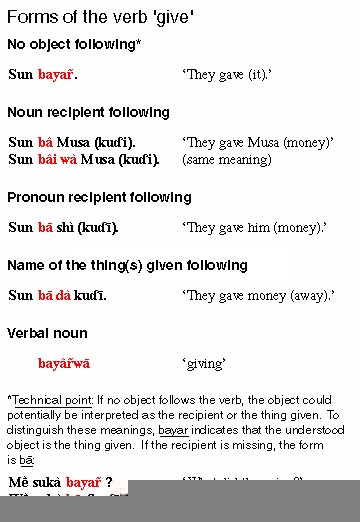

- The verb ba/bayar’give’: This is the most irregular verb in Hausa.

The table illustrates group (2) with bi ‘follow’ and ja ‘pull’ (monosyllabic verbs with short and long vowels respectively), (3) kira ‘call’ (representing also jira ‘wait for’ and biya ‘pay’), and (4) bari ‘leave’ (also representing sani ‘know’) and gani ‘see’.

| No object following | |

| Pronoun object following | |

| Noun object following | |

| Indirect object following |

Derived Verbs

What are derived verbs?

By saying a verb is “derived”, we mean that its base form has undergone some kind of change which shows the addition of special meaning to the base form. Hausa has four principal types of verb derivation. They are:

- -o verbs, which, roughly speaking, indicate “action toward the speaker” (so-called Grade 6 in the Verbal Grade System)

- -u verbs, which, roughly speaking, indicate that the subject of the verb is affected by the action which the verb indicates (so-called Grade 7 in the Verbal Grade System)

- Causative verbs, which, roughly speaking, indicate that someone or something is made to undergo the action which the verb indicates (so-called Grade 5 in the Verbal Grade System)

- Pluractional verbs, formed by doubling part of the verb, which, roughly speaking, indicate multiple action instances of an action.

Technical note on derived meanings of “base” forms of verbs (Grades 1, 2, 3, 4)

We can divide 99% of the verbs of Hausa into two groups–“base” and “derived”. In the terminology of the Hausa Grade System they are as follows:

| Base Verbs | Derived Verbs | ||||||||||||||

|

|

It turns out that Hausa can put a verb that has a particular base form into a different “base” form to give it a derived meaning! The main meanings that these “derived base” forms can provide are as follows, illustrated with some of the base forms from the examples in the table above.

| Grade 1 | apply the action to an object | rufa ‘put a covering on’ saya ‘buy for’ |

| Grade 2 | do a bit of; remove a part from the whole | yanka ‘cut a piece off’ karanta ‘read some of’ |

| Grade 3 | action reverts back to subject | rufa ‘be covered (with)’ karanta ‘be well-read’ |

| Grade 4 | action is done to completion; action is done in a direction away | yanke ‘cut in two, sever’ saye ‘buy up’ shige ‘pass (through)’, i.e. enter and go on |

-o Verbs: Action toward the speaker

Almost any verb in Hausa can take an -o form (also known as “ventive” and called “Grade 6” in the Hausa Grade System). The meaning of the -o form is sometimes characterized as “action toward the speaker”. This meaning works for most verbs that involve some sort of directional motion, such as shiga ‘enter, go in’ and its -o counterpart shigo ‘enter, come in’, but this meaning doesn’t work very well for verbs that involve no motion. A more comprehensive definition might be:

“An action which takes place or has its beginning at a distance from the speaker but which has its primary effect at the location of the speaker (or a location which the speaker is taking as a point of reference).”

Here are a few verbs contrasting the meaning in the base form and the -o form:

| Base verb | Base meaning | -o Verb | -o Verb meaning |

| shiga | ‘go in, enter’ | shigo | ‘come in’ |

| saya | ‘buy’ | sayo | ‘buy and bring (the thing(s) bought)’ |

| tambaya | ‘ask’ | tambayo | ‘ask and come back with the answer’ |

| bari | ‘leave’ (something and go) | baro | ‘leave’ (something behind and come) |

One forms an -o form from a base verb as follows:

- Replace the final vowel of the base with long -o. (If the verb is monosyllabic, retain the final vowel and insert -w- before the -o.)

- Give the resultant verb all High tones.

-o verbs are invariable, regardless of what type of object (or lack of object) follows:

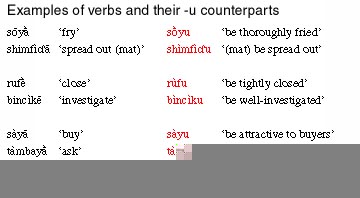

-u Verbs: Intransitive or ‘passive”

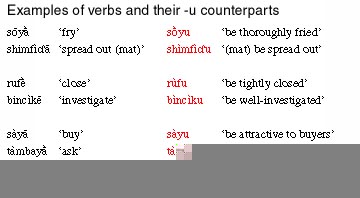

Most transitive verbs and some intransitive verbs can potentially take a -u form (called “Grade 7” in the Hausa Grade System). All -u derived verbs are intransitive.

The -u form is sometimes characterized as a “passive” because of the possiblity of translating some -u forms with an English passive, e.g. compare sun soya nama ‘they fried the meat’ with the -u counterpart nama ya soyu ‘the meat is fried’. Here, the object, nama ‘meat’, has become the subject of the -u derived form, parallel to the English active vs. passive translations.

However, if one has in mind the English passive as a characterization of the meaning of the Hausa -u form, “passive” is not a good characterization. English passive always implies the existence of an agent of the action, and the agent can be expressed by a “by” phrase, e.g. ‘the meat was fried by the chef’. A Hausa -u verb does not imply the existence of an agent (or better, one might say that the existence of an agent is not important when one uses a -u verb), and indeed it is not possible to express the agent of the action of a -u verb using something like an English “by” phrase. English passive is often used with no expressed agent, either because the specific agent is not known (“my car was stolen”–but I don’t know who did the stealing) or because the speaker wants to avoid mentioning the agent (“mistakes were made”). To convey this notion of “agentless passive”, Hausa uses a sentence with an impersonal subject, NOT the -u form.

A characterization of the -u form would be something like the following:

“The subject of a -u verb has undergone or has the potential for undergoing the action expressed by the verb. To the base meaning of the verb, the -u verb often adds a sense thoroughness or taking the action to its limit.”

Here are a few verbs contrasting the meaning in the base form and the -u form:

| Base verb | Base meaning | -u Verb | -u Verb meaning |

| soya | ‘fry’ | soyu | ‘be (thoroughly) fried’ |

| saya | ‘buy’ | sayu | ‘be well-sold, be attractive to buyers’ |

| bincike | ‘investigate’ | binciku | ‘be (thoroughly) investigated’ |

| bi | ‘follow’ | biyu | ‘be followable (a road); be well-traveled’ |

There are a few commonly used -u verbs which have meanings that may not be readily predicted from the meaning of the base verbs, though they all share the property of being intransitive, with the subject being the undergoer of the action:

| Base verb | Base meaning | -u Verb | -u Verb meaning |

| buga | ‘beat’ | bugu | ‘be drunk’ |

| fara | ‘begin’ | faru | ‘happen’ |

| gama | ‘finish; join’ | gamu (da) | ‘meet up (with)’ |

| raba | ‘divide’ | rabu (da) | ‘be divorced (from)’ |

| samu | ‘get’ | samu | ‘be obtainable’ |

| tambaya | ‘ask’ | tambayu | ‘be invulnerable (by taking special potions)’ |

| tara | ‘collect, gather’ | taru | ‘assemble, come together’ |

| yi | ‘do’ | yiwu | ‘be possible’ |

One forms an -o form from a base verb as follows:

- Replace the final vowel of the base with short -u. (If the verb is monosyllabic, retain the final vowel and insert -w- before the -u.)

- Place High tone on the last syllable with all preceding syllables Low.

Since all -u verbs are intransitive, they cannot take any kind of object and hence have the same form in all contexts.

Causative Verbs

In principle, most Hausa verbs could have a Causative counterpart (called “Grade 5” in the Hausa Grade System). In practice, only a limited number of verbs have commonly used causative counterparts. There are also a few verbs which are causative in form but which do not have a commonly used “base” form.

As the term “Causative” implies, the Causative form indicates that a person or object is “caused” to undergo the action of the base verb. One should not take the notion “cause” too literally, however. “Cause” in the literal sense would mean that the agent wielded some outside force that caused the event to happen (Hausa does have a separate verb sa ’cause’ to express this notion). A few example verbs will clarify the element of meaning that the Causative derivation adds.

| Base verb | Base meaning | Causative | Causative meaning |

| tsaya | ‘stop’ | tsayar | ‘stop, bring to a halt’ (i.e. “cause to stop”) |

| fita | ‘go out’ | fitar | ‘take out, remove’ (i.e. “cause to go out”) |

| saya | ‘buy’ | sayar | ‘sell’ (i.e. “cause to buy”) |

| koya | ‘learn’ | koyar | ‘teach (a subject)’ (i.e. “cause [someone] to learn (a subject)”) |

Many causative verbs can take any of three forms: (1) a “long” form, (2) a “short” form, and (3) a “pre-pronoun” form. All causative verbs can take a “long” form. A few seem never to appear in the latter two froms, e.g. koyar ‘teach’ in the table above.

(1) Long form (can be used in any context)

- Replace the final vowel of the base with -ar. (If the verb is monosyllabic, retain the final vowel and insert -y- before the -ar.)

- Give the resultant verb all high tones.

- If there is a direct object, insert the preposition da before the object. Note that if the object is pronoun, it is the Independent Pronoun rather than the Direct Object Pronoun.

Example from base verb tsaya ‘stop, come to a stop’

| No object | Na tsayar. | ‘I stopped (it).’ |

| Pronoun direct object | Na tsayar da ita. | ‘I stopped her.’ |

| Noun direct object | Na tsayar da akwiya. | ‘I stopped the goat.’ |

| Indirect object | Na tsayar masa (da) akwiya. | ‘I stopped the goat for him.’ |

(2) Short form (can be used only when a direct object follows)

- Drop the final vowel of the verb. (If the verb is monosyllabic, retain the final vowel and lengthen it if the base verb vowel is short.)

- Give the verb high tone.

- Insert the preposition da before the object. Note that if the object is pronoun, it is the Independent Pronoun rather than the Direct Object Pronoun.

Example from base verb tsaya ‘stop, come to a stop’

| Pronoun direct object | Na tsai da ita. | ‘I stopped her.’ |

| Noun direct object | Na tsai da akwiya. | ‘I stopped the goat.’ |

(3) Pre-pronoun form (can be used only with a pronoun direct object)

- Replace the final vowel of the base with -she. (If the verb is monosyllabic, retain the final vowel and lengthen it when adding -she.)

- Give the verb, including the -she ending, high tone.

- Use the Direct Object Pronouns.

Example from base verb tsaya ‘stop, come to a stop’

| Pronoun direct object | Na tsaishe ta. | ‘I stopped her.’ |

Technical note on dialect differences in the treatment of Causative “da”

Western and Northern dialects of Hausa treat the da as an ending on the verb, i.e. it is part of the verb. These dialects generally use only the form called “short” form causative here, treating it as a regular Hi-Lo-a verb (“Grade 1” in the Hausa Grade System). The forms for the Causative counterpart of tsaya ‘stop’ would be as follows:

| No object | Na tsaida. (with long final vowel on the verb) |

‘I stopped (it).’ |

| Pronoun direct object | Na tsaida ta. (with Direct Object Pronoun and lengthened final vowel on the verb) |

‘I stopped her.’ |

| Noun direct object | Na tsaida akwiya. | ‘I stopped the goat.’ |

| Indirect object | Na tsaida mishi akwiya. (with long final vowel on the verb) |

‘I stopped the goat for him.’ |

| Verbal noun | tsaidawa | ‘stopping’ |

Verbal Nouns

General Remarks

Verbal nouns are words based on verbs but which can be used as nouns. Verbal nouns can be used like any other noun, say, as a subject or object of a sentence. Hausa also requires a verbal noun as the form of the verb in the continuative. The examples below illustrate some uses of verbal nouns with the verbal noun tafiya ‘traveling’, which comes from the verb tafi ‘go, leave’.

| Subject of sentence: | Tafiya tana bud’e ido. | ‘Traveling opens the eyes.’ |

| Object of a verb: | Na sha tafiya. | “I traveled a lot.”, literally, ‘I drank traveling.’ |

| Verb in continuative: | Suna tafiya bana. | ‘They are traveling this year.’ |

Verbal nouns are two main types:

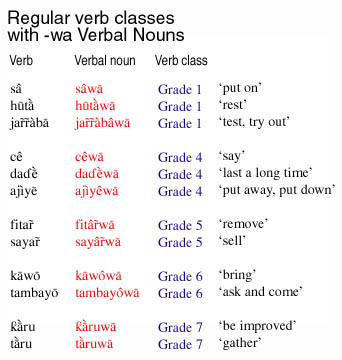

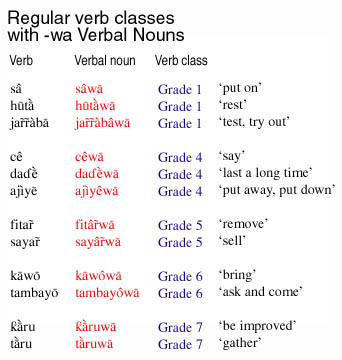

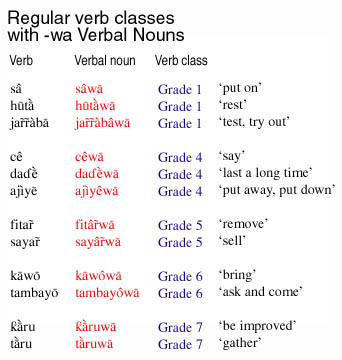

- -wa verbal nouns, which add an ending -wa to the base verb. If one were to simply count all the verbs of Hausa, the vast majority of those verbs would take -wa verbal nouns. However, many of the more frequently used verbs of Hausa do not use -waverbal nouns.

- non-wa verbal nouns, which change the final vowel and/or tone of the base verb, or, in some cases, are identical to the base verb. Many of the more frequently used verbs of Hausa require non-wa verbal nouns, and many verbs that have -wa verbal nouns have a second (in some cases, even a 3rd) verbal noun which is of a non-wa type.

-wa Verbal Forms

Form a -wa verbal noun in the following way:

- Add -wa to the base verb.

- If the last syllable of the verb has High tone, change the tone to Falling. (There is one exception: if the verb ends in -u, e.g. taru ‘gather’, the tone remains High.)

Classes of verbs taking of -wa Verbal Nouns

With fewer than 10 exceptions, all verbs with the following characteristics can use -wa verbal nouns:

- Verbs which begin with High tone and end in –a or –e

- The monosyllabic verbs sa ‘put on, cause’, ce ‘say’, and kai ‘carry’

- Verbs which have all high tones and end in –ar (“Causative” verbs)

- Verbs which have all high tones and end in –o (verbs indicating “action toward the speaker”)

- Verbs which begin in low tone and end in –u (“intransitive” or “passive” verbs)

In the Verbal Grade System, these are Grades 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7 respectively.

Verbal Grade System

Base Forms in the Verbal Grade System

The late F.W. Parsons devised a system of Hausa verb classification which has become the frame of reference for all Hausa scholars (see reference). This system groups verbs into seven Grades, where a “Grade” refers to the pattern of tones and final vowel which the verb carries. The seven Grades are as follows:

- Grade 1, Hi-Lo(-Hi)-a: Grade 1 are called “regular verbs” in -a elsewhere in this online grammar. Grade 1verbs of two syllables have Hi-Lo tones, verbs of three syllables have Hi-Lo-Hi, verbs of more than three syllables add additional Hi syllables to the beginning of the verb.

- Grade 2, Lo-Hi(-Lo)-a: All Grade 2 verbs are transitive and end in long -a. Grade 2 verbs are called Variable Vowel Verbs elsewhere in this online grammar. Two syllable Grade 2 verbs have Lo-Hi tones, verbs of three syllables have Lo-Hi-Lo, verbs of more than three syllables add additional Lo syllables to the beginning of the verb.

- Grade 3, Lo-Hi(-Lo)-a: All Grade 3 verbs are intransitive and end in short -a. Grade 3 verbs are grouped with other intransitive verbs elsewhere in this online grammar. Two syllable Grade 3 verbs have Lo-Hi tones, verbs of three syllables have Lo-Hi-Lo, verbs of more than three syllables add additional Lo syllables to the beginning of the verb.

- Grade 4, Hi-Lo(-Hi)-e: Grade 4 are called “regular verbs” in -e elsewhere in this online grammar. Grade 4verbs of two syllables have Hi-Lo tones, verbs of three syllables have Hi-Lo-Hi, verbs of more than three syllables add additional Hi syllables to the beginning of the verb.

- Grade 5, All Hi tones + -ar or no final vowel + da: Grade 5 verbs are called Causative Verbselsewhere in this online grammar.

- Grade 6, All Hi tones + -o: Grade 6 verbs are called -o verbs elsewhere in this online grammar.

- Grade 7, Lo…Hi–u: Grade 7 verbs are called -u verbs elsewhere in this online grammar. The final tone of Grade 7 verbs is Hi, with all preceding syllables Lo.

Objects with the Verbal Grades

An important feature differentiating the verbal grades is the forms that verbs take before objects. Parsons spoke of four contexts, which he called A, B, C, and D. The table below lays out what those contexts are and the form each grade takes in each context. The highlighted links open windows which show illustrative verbs of each grade in each context from the relevant sections of the online grammar.

| A no object |

B pronoun object |

C noun object |

D indirect object |

|

| Grade 1 | Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -a |

Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -a |

Hi-Lo(-Lo) short final -a |

Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -a |

| Grade 2 | Lo-Hi(-Lo) long final -a |

(Lo-)Lo-Hi long final -e |

(Lo-)Lo-Hi short final -i |

varies |

| Grade 3 | Lo-Hi(-Lo) short final -a* |

(all intransitive) | (all intransitive) | varies |

| Grade 4 | Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -e |

Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -e |

Hi-Lo(-Lo) short final -e |

Hi-Lo(-Hi) long final -e |

| Grade 5 | All Hi-ar | – All Hi-ar da – All Hi root da – All Hi-she |

– All Hi-ar da – All Hi root da |

All Hi-ar |

| Grade 6 | All Hi-o | All Hi-o | All Hi-o | All Hi-o |

| Grade 7 | (Lo-)Lo-Hi short final -u |

(all intransitive) | (all intransitive) | (all intransitive) |

*A substantial number of two syllable intransitive verbs which could be considered Grade 3 have Hi-Hi tones, e.g. kwana ‘spend the night’, b’uya ‘hide’. Most of these have a heavy first syllable whereas most Lo-Hi Grade 3 verbs have a light first syllable.

Basic vs. Derived Grades

Parsons differentiated between what he considered to be “basic” Grades, viz. Grades 1-3, and “derived” grades, viz. Grades 4-7. This division refers in part to predictability in form, but primarily to meaning.

Predictability: Among Grades 1-3, there seems to be little, if anything, about the meaning of the verbs which allows one to predict which Grade they will fall into, i.e. there are Grade 1 verbs that are transitive but have meanings that are similar to Grade 2 verbs (all of which are transitive), and there are Grade 1 verbs that are intransitive but have meanings that are similar to Grade 3 verbs (all of which are intransitive):

- gaya ‘tell’ is a Grade 1 verb, whereas fad’a ‘say’ is a Grade 2; yanka ‘cut’ is a Grade 1 verb, whereas sara ‘chop’ is a Grade 2

- tsaya ‘stop, come to a halt’ is a Grade 1 verb, whereas sauka ‘get down’ is a Grade 3

Parsons also noted that Grade 4 verbs form a sort of mixed category. There are some Grade 4 verbs which seem to have basic meanings that would not differentiate them in any systematic way from verbs in Grades 1-3:

- ajiye ‘put away, deposit’ is a Grade 4 verb, whereas saka/sa ‘put down, put on’ is a Grade 1

- gane ‘understand, recognize’ is a Grade 4 verb, whereas fahimta ‘understand, comprehend’ is a Grade 2

- gode ‘thank’ is a Grade 4 verbs, whereas yarda ‘agree’ is a Grade 3

It is, however, possible to change verbs from Grades 1-3 into Grade 4 to create derived meanings (see just below).

Meaning: The main reason for making a distinction between basic and derived grades is that, by and large, when a root is found in one of the derived grades, there is a fairly constant element of meaning associated with the Grade form, an element of meaning which is absent in the basic grades. This is particularly clear in Grades 5-7. Click on the highlighted links for a discussion of meaning in the online grammar:

- Grade 5: “causative”

- Grade 6: “action toward the speaker”

- Grade 7: “intransitive” or “passive”

As noted, Grade 4 is mixed between “basic” and “derived” meanings. As it turns out, Grades 1-3 also have this property, making a strict division between “basic” and “derived” grades questionable.

Technical note on derived meanings of “base” forms of verbs (Grades 1, 2, 3, 4)

We can divide 99% of the verbs of Hausa into two groups–“base” and “derived”. In the terminology of the Hausa Grade System they are as follows:

| Base Verbs | Derived Verbs | ||||||||||||||

|

|

It turns out that Hausa can put a verb that has a particular base form into a different “base” form to give it a derived meaning! The main meanings that these “derived base” forms can provide are as follows, illustrated with some of the base forms from the examples in the table above.

| Grade 1 | apply the action to an object | rufa ‘put a covering on’ saya ‘buy for’ |

| Grade 2 | do a bit of; remove a part from the whole | yanka ‘cut a piece off’ karanta ‘read some of’ |

| Grade 3 | action reverts back to subject | rufa ‘be covered (with)’ karanta ‘be well-read’ |

| Grade 4 | action is done to completion; action is done in a direction away | yanke ‘cut in two, sever’ saye ‘buy up’ shige ‘pass (through)’, i.e. enter and go on |

Some problems with the grade system

The Grade system provides a frame of reference for all but a handful of Hausa verbs. All Hausa specialists use it, and there is no question as to its usefulness and the fact that it reflects real categories of Hausa verbs. Nonetheless, it does have some shortcomings.

- Hausa verbs that do not fit into the system: Although the Grade system accounts for probably 99% of the verbs in a Hausa dictionary, there are some important categories of verbs that it does not accommodate, including some of the most frequently used verbs in Hausa. In particularly, it does not account for any of the 10 or so monosyllabic verbs nor any non-derived verbs ending in the vowels –i or –u, including the important verbs sani‘ know’, bari ‘leave’, and gani ‘see’. Parsons recognized this and published an article in the early 1970’s attempting to incorporate such verbs (see reference), but one gets the feeling that he is pounding square pegs into round holes. See a discussion of the classes of verbs which do not fit the Grade System.

- Missed generalizations: The Grade System as originally laid out by Parsons misses some important generalizations about verb classification. The most obvious is the fact that Grades 2 and 3 in the Grade System would be categories as distinct as, say, Grades 2 and 6, whereas Grades 2 and 3 are essentially identical in form, with any differences predictable on the basis of the fact that Grade 2 verbs are all transitive and Grade 3 verbs are all intransitive. Moreover, as noted in the section above this, the “basic” vs. “derived” Grade division misses the fact that the “basic” Grades 1-3 actually have derivational properties as well. These and other problems with the Grade System have been covered by Paul Newman (see reference).

- The Grade System as a learner’s framework: (This comment is not a critique of the Grade System per se, but it will serve as an explanation for why I did not choose the Grade System as the organizational system for verbs in the online grammar.) The Grade System focuses on an idealized formal system of verb classification but says very little about the way verbs are actually used. For example, as noted in the first bulleted point above, the Grade System does not accommodate some of the most commonly used verbs in Hausa. On the other side of the coin, by focusing on formal derivational possibilities, it leads to a discussion of verb forms that rarely occur and even for a native Hausa speaker, would have highly marked meanings. For example, Grade 7 verbs are generally used only with transitive base verbs, but the question arises as to whether intransitive base verbs can be put into Grade 7. The answer is yes, in such forms as shigu ‘be crowed’ (“be well-entered”) from shiga ‘enter’, but one could spend years in Hausaland and read thousands of pages of text before encountering such a form. Next, although the Grade System gives a way to pigeonhole verb forms, it becomes a distraction in learning how to use verbs. The verbs k’ara ‘increase’ and k’are ‘finish’ are Grade 1 and 4 forms respectively of the same root, but in learning Hausa, it makes more sense to simply learn them as separate words with separate meanings than to think of them in terms of the formal pigeonholes they fit into. Finally, reference to the Grade System framework obscures cross-grade generalizations, in particular that Grades 1 and 4 are identical in all respects except final vowel, which, from the point of view of constructing sentences using these verbs, is of no importance.

Reference

Paul Newman, “Grades, vowel-tone classes and extensions in the Hausa verbal system,” Studies in African Linguistics 4:297-346, 1973.

F.W. Parsons, “The verbal system in Hausa,” Afrika und Ubersee, 44:1-36, 1960.

F.W. Parsons, “Suppletion and neutralization in the verbal system of Hausa,” Afrika und Ubersee 55:49-97, 188-208, 1971/72.