Hausa Sentences Expressing “be”

Hausa has no verb ‘be’. It uses several different types of constructions to express concepts for which English uses the single verb ‘be’.

Identification

‘I am a student’, ‘that is a book’

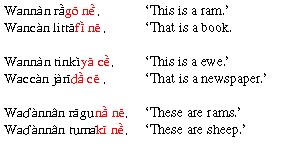

Basic Identification Sentences: NE and CE

Hausa sentences that express identification of a person or thing use a word ce if the person or thing being identified is feminine singular and a word ne if the person or thing being identified is masculine singular or is plural(regardless of gender of the singular). In a simple statement, ne or ce is at the end of the sentence. (Although one might translate ne or ce as ‘is’, ‘are’, and so on, these words are NOT verbs).

| Masculine nouns | Bala d’alibi ne. Wannan rago ne. Wancan littafi ne. |

‘Bala is a student.’ ‘This is a ram.’ ‘That is a book.’ |

| Feminine nouns | Zainab d’aliba ce. Wannan tinkiya ce. Waccan jarida ce. |

‘Zainab is a student.’ ‘This is a ewe.’ ‘That is a newspaper.’ |

| Plural nouns | Bala da Zainab d’alibai ne. Wad’annan raguna ne. Wad’annan tumaki ne. Wad’ancan littattafai ne. Wad’ancan jaridu ne. |

‘Bala and Zainab are students.’ ‘These are rams.’ ‘These are sheep.’ ‘Those are books.’ ‘Those are newspapers.’ |

Why ne and ce are not verbs:

Technical writings on Hausa refer to ne and ce as “stabilizers” (the term used by the great Hausa scholar, F.W. Parsons) or “copulas” (the term used by most linguists today). There are a number of reasons for not calling ne and ce “verbs”:

- The subject pronouns which go with all other verbs do not go with ne or ce.

- Following from the first point, since Hausa uses subject pronouns to express “tense” or mood (completedness, futureness, imperative or exhortation, etc.), none of these overtly expressed distinctions are available with neand ce.

- No verbs have separate forms to show gender agreement, whereas ce is restricted to feminine singular and ne to masculine singular and any plural.

- Verbs go after the subject; ne and ce go at the end of the sentence, at least in simple statements of identification.

- Ne and ce are invariable. One cannot, for example, make them into nouns meaning ‘being’.

- Ne and ce can be omitted in many contexts–identification can really be accomplished just by stating a subject followed by an identifying noun. With the exception of the verb ‘do’ in specific contexts, verbs must be expressed since they are fundamental words in their sentences.

Hausa is unusual among its sister Chadic languages in having an overt copula, i.e. ne or ce. Most Chadic languages form identificational sentences by juxtaposing the subject noun and the predicate noun with no further marking. “Old Hausa” undoubtedly did the same, a fact which is still evident in many fixed and presumably archaic expressions, especially proverbs such as the following, where there is no ne or ce.

| Tambarin talaka cikinsa. Sarautar Allah kare a bakin zomo. Amfanin abin ado d’aurawa. Gwanin dokin wanda yake kansa. Wutsiyar tsaka mai gautsi. |

‘The drum of a commoner is his belly.’ ‘The reign of Allah is a dog in a hare’s mouth.’ ‘The use of finery is the wearing (of it).’ ‘The expert horseman is the one who’s on it.’ ‘The tail of a gecko is a fragile thing.’ |

Ne and ce have their origin in the demonstrative system, and Hausa still uses related elements in demonstrative-like functions, e.g. possessives such as na-sa ‘his’ (that-of-him) referring to a masculine thing, ta-sa ‘his’ (that-of-him) referring to a feminine thing. (In Western dialects of Hausa, the copula is actually na and ta rather than ne and ce.) While it is not entirely clear how the demonstratives became copulas, it undoubtedly started with identificational sentences like ‘my book is this one’, with eventual weakening in the meaning of the demonstrative until it came to be simply a marker of an identificational sentence.

Technical Note on Gender Conflict in Ne/Ce Sentences

Since every noun in Hausa has its own grammatical gender, and since a ne/ce sentence can have two nouns, it is possible that those nouns will not have the same gender. The question thus arises as to whether ne or ce will agree in gender to the first noun (the “subject”) or the second noun (the “predicate”). A number of technical linguistic works on Hausa have discussed this. I will not discuss the details of any of these works here. Suffice it to say that either ne or ce is possible in such sentences, and there is no grammatical rule that determines the choice. Here are some examples from Junaidu (1995):

| Wando (irin) tufa ne. | Wando (irin) tufa ce. | ‘Pants are (a type of) clothing’. |

- wando (m) ‘pants’

- tufa (f) ‘article of clothing’

| Dabba da na gani rak’umin sarki ce. | Dabba da na gani ra’kumin sarki ne. | ‘The animal that I saw was the camel of the chief.’ |

- dabba (f) ‘animal’

- rak’umi (m) ‘camel’

Junaidu, who is the only linguistically trained native speaker of Hausa to have specifically addressed this issue, claims that the difference “is on what element one wants to focus on”. That is, the noun with which ne or ce agrees is the element which the speaker is focusing on. Thus, in the first example above, ne indicates that the speaker is stressing the fact that PANTS are a type of clothing where ce indicates that pants are a type of CLOTHING, not something with some other function.

References

- Junaidu, Ismail. 1995. “Nature of Hausa equational sentences,” Paper presented at the 5th International Conference on Hausa Language, Literature, and Culture, Bayero University, Kano, 7-12 August 1995. [so far not published]

- Parsons, F.W. 1963. “The operation of gender in Hausa: stabilizer, dependent nominals and qualifiers,” African Language Studies 4:166-207.

- Schachter, Paul. 1966. “A generative account of Hausa ne/ce.” Journal of African Languages 5:34-53.

Technical Note on the Origin of Ne/Ce Sentences

Hausa is unusual among its sister Chadic languages in having an overt copula, i.e. ne or ce. Most Chadic languages form identificational sentences by juxtaposing the subject noun and the predicate noun with no further marking. “Old Hausa” undoubtedly did the same, a fact which is still evident in many fixed and presumably archaic expressions, especially proverbs such as the following, where there is no ne or ce.

| Tambarin talaka cikinsa. Sarautar Allah kare a bakin zomo. Amfanin abin ado d’aurawa. Gwanin dokin wanda yake kansa. Wutsiyar tsaka mai gautsi. |

‘The drum of a commoner is his belly.’ ‘The reign of Allah is a dog in a hare’s mouth.’ ‘The use of finery is the wearing (of it).’ ‘The expert horseman is the one who’s on it.’ ‘The tail of a gecko is a fragile thing.’ |

Ne and ce have their origin in the demonstrative system, and Hausa still uses related elements in demonstrative-like functions, e.g. possessives such as na-sa ‘his’ (that-of-him) referring to a masculine thing, ta-sa ‘his’ (that-of-him) referring to a feminine thing. (In Western dialects of Hausa, the copula is actually na and ta rather than ne and ce.) While it is not entirely clear how the demonstratives became copulas, it undoubtedly started with identificational sentences like ‘my book is this one’, with eventual weakening in the meaning of the demonstrative until it came to be simply a marker of an identificational sentence.

Tones of Ne and Ce

Ne and ce always have tone opposite the preceding syllable, i.e. High tone after Low and Low tone after High. (The grave accent, ` , above a vowel shows that the syllable has Low tone.)

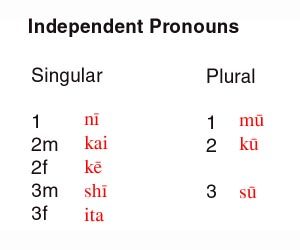

Identificational Sentences with Pronoun Subject

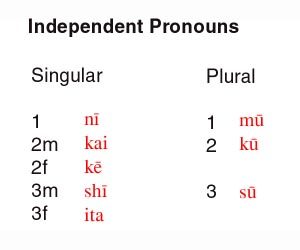

If the subject of an identificational sentence is a pronoun, the independent pronoun is used.

| Ni d’alibi ne. Ni d’aliba ce. |

‘I am a (male) student.’ ‘I am a (female) student.’ |

Mu d’alibai ne. | ‘We are students.’ |

| Kai shugaba ne. | ‘You (m) are the leader.’ | Ku malamai ne. | ‘You (pl) are teachers.’ |

| Ke malama ce. | ‘You (f) are a teacher.’ | ||

| Shi sarki ne. | ‘He is the chief.’ | Su sarakuna ne. | ‘They are chiefs.’ |

| Ita sarauniya ce. | ‘She is the queen.’ |

It’s…’: Identificational Sentences with No Expressed Subject

A noun or pronoun can be used alone with ne or ce to mean ‘its …’ or ‘they’re …’.

| Bala ne. Rago ne. Littafi ne. Ni ne. Kai ne. Shi ne.Zainab ce. Tinkiya ce. Jarida ce. Ni ce. Ke ce. Ita ce.Zainab da Bala ne. Tumaki ne. Littattafai ne. Mu ne. Ku ne. Su ne. |

‘It’s Bala.’ ‘It’s a ram.’ ‘It’s a book.’ ‘It’s me.’ (male speaking) ‘It’s you.’ (speaking to a male) ‘It’s him.’It’s Zainab. ‘It’s a ewe.’ ‘It’s a newspaper.’ ‘It’s me.’ (female speaking) ‘It’s you.’ (speaking to a female) ‘It’s her.’‘It’s Zainab and Bala.’ ‘They’re sheep.’ ‘They’re books.’ ‘It’s us.’ ‘It’s you.’ (speaking to a group) ‘It’s them.’ |

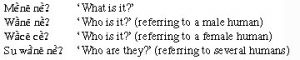

‘What is it?’, ‘Who is it?’: Identificational Questions

Basic identificational questions have the following forms:

If the name of the person or thing asked about is expressed, it usually follows the expressions above unless it is a pronoun, in which case it usually precedes:

| Mene ne wannan? Mene ne “turmi”?Wane ne wancan? Wane ne Sir Alhaji Ahmadu Bello? Shi wane ne?Wace ce waccan? Wace ce Sarauniya Daurama? Ita wace ce?Su wane ne wad’ancan mutane? Ku su wane ne? |

‘What is this?’ ‘What is a “turmi”?‘Who is that?’ (referring to a male human) ‘Who was Sir Alhaji Ahmadu Bello?’ ‘Who is he?’‘Who is that?’ (referring to a female human) ‘Who was Queen Daurama?’ ‘Who is she?’‘Who are those people?’ ‘Who are you?’ (speaking to a group) |

In everyday speech, one often hears contracted forms Me ye? ‘What is it? and Wa ye? ‘Who is it?’ Parallel to Wace ce? ‘Who is it?’, which can be used when one knows that the referent is female, one occasionally hears Mece ce? ‘What is it (feminine)?’ when it is known that the thing in question is of feminine gender.

Negative Identifcational Sentences

To express the notion of “not be”, ba with long vowel and low tone precedes the negated part and ba with high tone and short vowel follows it. Ne or ce follow the second ba. The ba…ba can surround just a noun or pronoun to mean ‘it’s not …’, ‘he’s not …’, ‘she’s not …’.

| Bala ba malami ba ne. Wannan ba rago ba ne. Ni ba d’alibi ba ne. Ba Bala ba ne. Ba shi ba ne.Zainab ba malama ba ce. Wannan ba tinkiya ba ce. Ke ba d’aliba ba ce. Ba Zainab ba ce. Ba ita ba ce.Bala da Zainab ba d’alibai ba ne. Wad’ancan ba tumaki bane. Su ba malamai ba ne. Ba littattafai ba ne. Ba mu ba ne. |

‘Bala is not a teacher.’ ‘This is not a ram.’ ‘I am not a student.’ ‘It’s not Bala.’ ‘It’s not him.’‘Zainab is not a teacher.’ ‘This is not a ewe.’ ‘You (f) are not a student.’ ‘It’s not Zainab.’ ‘It’s not her.’‘Bala and Zainab are not students.’ ‘These are not sheep.’ ‘They are not teachers.’ ‘They’re not books.’ ‘It’s not us.’ |

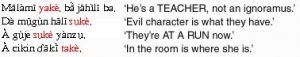

Emphasizing Words in Identificational Sentences

In order to put emphasis on the subject of an identificational sentence, ne or ce follows the subject. This turn of phrase is particularly common in sentences of the following type, where the person thing to be identified is either seen or known in advance. The person or thing is first referred to by a demonstrative ‘this’ or ‘that’, then the identificational sentence has a pronoun subject with ne or ce following:

| Wannan, ita ceakwiya. Wannan, shi nebunsuru. Wad’annan, su neshanu. |

‘This one, IT is a goat.’ = ‘THIS ONE is a goat.’ ‘This one, IT is a billy-goat.’ = ‘THIS ONEis a billy-goat.’ ‘These, THEY are cows.’ = ‘THESE are cows.’ |

Name as Predicate: ‘My name is Zainab’; ‘what is your name?’

In English, sentences like ‘my teacher is John’ and ‘my name is John’ have identical form. In Hausa, they are different. Whereas the first would be a normal identificational sentence ending in ne or ce (malamina John ne), the latter, with “name” as the subject and a proper name as predicate, never ends in ne or ce–one simply says ‘… name’ + the proper name.

| Sunana D’anladi. Sunansa Musa.Sunana Zainab. Sunanta Hadiza. |

‘My name is D’anladi.’ ‘His name is Musa.’‘My name is Zainab.’ ‘Her name is Hadiza.’ |

Likewise, in English, questions like ‘what is your job?’ and ‘what is your name?’ have identical form. In Hausa, the first would be a regular identificational question asking ‘what is …?’ (mene ne aikinka?). The latter is most commonly expressed using yaya?, literally ‘how?’

| Yaya sunanka? Yaya sunanki?Yaya sunansa? |

‘What’s your name?’ (speaking to a male) ‘What’s your name?’ (speaking to a female)‘What’s his name?’ |

(Some speakers do use mene ne? in name questions, i.e. Mene ne sunanka? ‘What’s your name?’. Others use wa(ne ne)? ‘who?’, i.e. Wa sunanka? ‘What is your name?’)

A Quantity as Predicate: ‘there are two of us’; ‘he has two wives’; ‘my arm is 24 inches long’

In a number of expressions where English uses a number to modify a noun or pronoun, Hausa uses a construction where the number is in the predicate of an identificational sentence. These sentences are something like stilted or archaic constructions such ‘we are two’ (= ‘there are two of us’), ‘his wives are two’ (= ‘he has two wives’).

| Q: Ku nawa ne? A: Me biyu ne.D’alibai hamsin ne. |

‘How many of you are there?’ (‘You are how many?’) ‘There are two of us.’ (‘We are two.’)‘There are fifty students.’ (‘The students are fifty.’) |

If the subject includes a possessive, ne or ce is absent.

| Q: Matanka nawa? A: Matana biyu. |

Q: How many wives do you have? (Your wives are how many?) A: I have two wives. (My wives are two.) |

| Q: Shekarunsa nawa? A: Shekarunsa sha biyu. |

Q: How old is he? (His years are how many?) A: He is 12 years old. (His years are twelve.) |

| Tsawon hannuka inci ashirin da hud’u. | Your arm is 24 inches long. (The length of your arm is 24 inches.) |

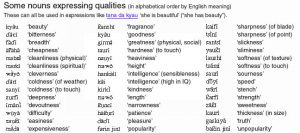

Sentences with Qualities as Predicates

General Remarks on Qualities as Predicates in Hausa

In English, nearly any quality can be attributed to a noun in a sentence of the form ‘she is …’ with an adjective in place of the dots, e.g. ‘she is tall ~ beautiful ~ smart ~ devout ~hungry ~ lazy ~ tired’, etc. Hausa sentences translatable as English ‘she is …’ take a number of forms depending on the quality. Only a minority of such sentences involve adjectives. Here are the main ways Hausa expresses qualities as predicates.

Adjectives as predicates of ‘be’ (ne/ce) sentences

Hausa does have a small number of true, “simple” (= “non-derived”) adjectives. These mostly express size, age, or color. Sentences with true adjectives have the form “subject + adjective + ne/ce“.

| Ni dogo ne. Jaka ja ce. |

‘I am tall.’ ‘The bag is red.’ |

Nouns of quality in ‘have’ sentences

The majority of “quality words” in Hausa are nouns. Hausa uses these nouns in ‘have’ sentences, literally saying, “She has beauty,” rather than saying, “She is beautiful.”

| Tana da kyau. Wuk’a tana da kaifi. |

‘She is beautiful.’ ‘The knife is sharp.’ |

= ‘She has beauty.’ = ‘The knife has sharpness.’ |

Nouns referring to a person with certain characteristics

Hausa expresses ethnicity or nationality and some inherent physical characteristics using nouns referring to a person of that type. These nouns appear as the the predicate of ne/ce identificational sentences.

| Ni Bahaushe ne. Ita Bafilatana ce. Audu makaho ne. Kai rago ne. Kande wawa ce. |

‘I am Hausa.’ ‘She is Fulani.’ ‘Audu is blind.’ ‘You are lazy.’ ‘Kande is foolish.’ |

= ‘I am a Hausa person.’ = ‘She is a Fulani person.’ = ‘Audu is a blind man.’ = ‘You are a lazy person.’ = ‘Kande is a fool.’ |

Nouns expressing physical or emotional sensations

Physical and emotional sensations are expressed with nouns following the verb ji ‘feel’.

| Ina jin tsoro. Kina jin sanyi? Muna jin yunwa. Audu ya ji kunya. |

‘I am afraid.’ ‘Are you cold?’ ‘We are hungry.’ ‘Audu was ashamed.’ |

= ‘I feel fear.’ = ‘Do you feel coldness?’ = ‘We feel hunger.’ = ‘Audu felt shame.’ |

Verbs or “action nouns” expressing physical or emotional conditions

Some physical or emotional states are expressed with verbs or with “action nouns” following the verb yi ‘do’ (which can be omitted in the continuative).

| Na gaji. Kofi ya cika. Riga ta bushe. Mun yi murna. Kande ta yi bak’in ciki. Yara suna barci. |

‘I am tired.’ ‘The cup is full.’ ‘The shirt is dry.’ ‘We were happy.’ ‘Kande was unhappy.’ ‘The children are asleep.’ |

= ‘I tired.’ = ‘The cup filled.’ = ‘The shirt dried.’ = ‘We did happiness.’ = ‘Kande did unhappiness.’ = ‘The children are (doing) sleep.’ |

Adjectives as Predicate

‘the bag is red’, ‘I am tall’

Basic Pattern: ‘the bag is red’

Sentences with an adjective as predicate follow the same patterns as identificational sentences with a noun as predicate, the only difference being that adjectives must agree in gender or plurality with the subject. Sentences with adjectives as predicate have the following characteristics:

- The order is subject – adjective.

- The sentence ends in ce if the subject is feminine singular or ne if the subject is masculine singular or any plural.

- The adjective must agree in gender or plurality with the subject.

| Masculine subject | Rago fari ne. Bala dogo ne. Kofi ja ne. Nama dafaffe ne. |

‘The ram is white.’ ‘Bala is tall.’ ‘The cup is red.’ ‘The meat is boiled.’ |

| Feminine subject | Tinkiya fara ce. Zainab doguwa ce. Jaka ja ce. Gyad’a dafaffiya ce. |

‘The ewe is white.’ ‘Zainab is tall.’ ‘The bag is red.’ ‘The peanuts are boiled.’ |

| Plural subject | Tumaki farare ne. Wad’annan d’alibai dogwaye ne. Jakunkuna jajaye ne. Kayan ciki dafaffu ne. |

‘The sheep are white.’ ‘These students are tall.’ ‘The bags are red.’ ‘The innards are boiled.’ |

Pronoun Subjects: ‘I am tall’

A pronoun subject of an adjectival sentence is expressed by the independent pronoun.

| Ni dogo ne. Kai dogo ne. Shi gagararrene.Ni doguwa ce. Ke doguwa ce. Ita gagararriyace.Mu dogwayene. Ku dogwayene. Su gagararrune. |

‘I am tall.’ (male speaking) ‘You (m) are tall.’ ‘He is rebellious.’‘I am tall.’ (female speaking) ‘You (f) are tall.’ ‘She is rebellious.’‘We are tall.’ ‘You (pl) are tall.’ ‘They are rebellious.’ |

Negative Adjectival Sentences: ‘I am not short’

A negative adjectival sentences has ba with low tone and long vowel before the adjective and ba with short vowel and high tone after it.

| Sa ba fari ba ne. Kofi ba ja ba ne. Bala ba gajere ba ne. Ni ba gajere ba ne. Shi ba gagararre bane.Saniya ba fara ba ce. Jaka ba ja ba ce. Zainab ba gajere bace. Ni ba gajeriya ba ce. Ita ba gagararriya bace.Shanu ba farare ba ne. Jakunkuna ba jajayeba ne. Mu ba gajeru ba ne. Su ba gagararru ba ne. |

‘The bull is not white.’ ‘The cup is not red.’ ‘Bala is not short.’ ‘I am not short.’ (male speaking) ‘He is not rebellious.’‘The cow is not white.’ ‘The bag is not red.’ ‘Zainab is not short.’ ‘I am not short.’ (female speaking) ‘She is not rebellious.’‘The cows are not white.’ ‘The bags are not red.’ ‘We are not short.’ ‘They are not rebellious.’ |

Comparison

In English, sentences involving comparison use the verb ‘be’ with a word or phrase in the predicate specifying the type of comparison:

- Greater than some standard: ‘he is taller than me’, ‘he is more patient than me’

- Not as great as some standard: ‘he is less tall than me’

- Equal to some standared: ‘he is as tall as me’

- Exceeding some (desired) standard: ‘the tea is too hot (for me to drink)’

In Hausa, the specification of the type of comparison is in the verb rather than the expression involving the quality.

Comparatives: ‘you are taller than me’

Comparatives use the verb fi ‘exceed, surpass’. Sentences with fi have the following form:

Subject + subject pronoun + fi (+ person/thing being compared) (+ quality for comparison)

Fi is a stative verb and hence is normally in the completive. (See a list of quality words that could appear in comparative constructions.) Either the person/thing being compared and/or the quality of comparison may be omitted, with context determining the specific comparison one has in mind.

| Ka fi ni tsawo. Rak’umi ya fi jaki k’arfi.Haka yafi kyau. Wannan ya fiwancan. Wannan ya fi. |

‘You are taller than me.’ (“You exceed me [in] height.”) ‘A camel is stronger than a donkey.’ (“A camel exceeds a donkey [in] strength.”) ‘That‘s better.’ (“Thus exceeds [in] goodness.”) ‘This is [better] than that.’ (“This one exceeds that one.”) ‘That‘s [better].’ (‘This one exceeds.’) |

‘Less than’ Comparatives: ‘I am less tall than you’

Comparatives expressing ‘less’ can use either the verb kai ‘be equal to’ in the negative or the verb kasa ‘be less than’ (which, in other contexts, means ‘fail, be unable’). Sentence structure and use of tense marking is the same as for fi ‘exceed, surpass’.

| Na kasa ka tsawo. = Ban kai ka tsawo ba.Bakwai ya kasa takwas. = Bakwai bai kai takwas ba. |

‘I am less tall than you.’ (“I am less than you [in] height.’) = ‘I am not equal to you [in] height.’‘Seven is less than eight.’ = ‘Seven is not as much as eight.’ |

“Excessives”: ‘the tea is too hot‘

Hausa expresses the notion of “too” in the sense of “excessively” with the verb yi ‘do’. There are two possible ways to use yi this way. (See remarks on fi ‘exceed, surpass’ for comments on verb tense and a list of quality words.)

- Quality + yi + yawa ‘abundance:

| Zafin shayi ya yi yawa. Duhun kai ya yi yawa a nan. |

‘The tea is too hot.’ (“The heat of the tea doesabundance.”) ‘There is too much ignorance here.’ (“Darkness of head does abundance here.”) |

2. Subject + yi (+affected person/thing) + quality:

| Shayi ya yi zafi. Wannan riga ta yi mini tsada. |

‘The tea is too hot.’ (“The tea does heat.”) ‘This robe is too expensive for me.’ (“This robe does to me expensiveness.”) |

Yi does not really mean ‘be too much’. The notion of “excessiveness” comes from context and the knowledge of desirability of particular properties. Yi + quality word is often more or less equivalent to the ‘have’ construction with a quality word, e.g.

| Wannan riga ta yi kyau. Wannan riga tana dakyau. |

‘This robe is beautiful.’ (“This robe does beauty.”) ‘This robe is beautiful.’ (“This robe has beauty.’) |

Locative: ‘the cup is in the cupboard’

Basic Pattern for Locative Sentences: ‘I am at home’, ‘the cup is in the cupboard”

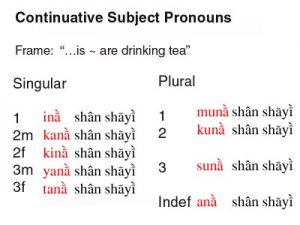

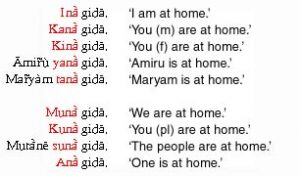

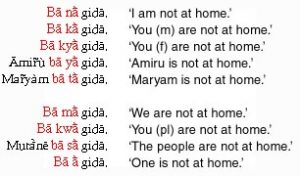

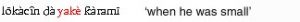

A sentence which states the location of a person or thing uses the continuative pronouns followed directly by the the location. Below is the entire paradigm with gida ‘home’ as the predicate. Note that there is no preposition expressing ‘at’–the continuative pronouns include the notion ‘at, in, on’.

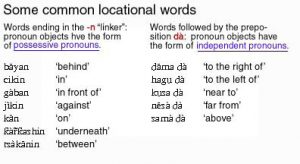

Although the “all purpose” locative prepostion a ‘at, in, on’ CANNOT follow the continuative pronouns, locative sentences can use “prepositions” which express more specific locations.

| Kofi yana cikin kwaba. Goro yana tsakanin kyandir da kwalaba. Ina gabanka. Bashir yana dama da Bala.Madara tana cikin firji. Kina tsakanina da Kande. Kujera tana kusa da k’ofa. Tana dama da ke.Kofuna suna cikin kwaba. ‘Yam mata suna kan tabarma. Muna hagu da ita. |

‘The cup is in the cupboard.’ ‘The kola is between the candle and the bottle.’ ‘I am in front of you.’ ‘Bashir is to the right of Bala.’‘The milk is in the refrigerator.’ ‘You (f) are between me and Kande.’ ‘The chair is near the door.’ ‘She is to the right of you.’‘The cups are in the cupboard.’ ‘The girls are on the mat.’ ‘We are to the left of her. |

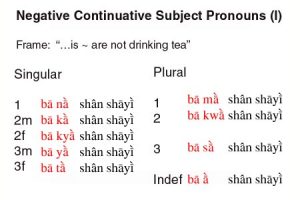

Negative Locative Sentences

Negative locative sentences use the negative continuative pronouns also used with verbs.

Although the “all purpose” locative preposition a ‘at, in, on’ CANNOT follow the negative continuative pronouns, locative sentences can use “prepositions” which express more specific locations.

| Kofi ba ya cikin kwaba. Goro ba ya tsakanin kyandir da kwalaba. Ba ka gabana. Bashir ba ya dama da Bala.Madara ba ta cikin firji. Ba kya tsakanina da Kande. Kujera ba ta kusa da k’ofa. Ba ta dama da ke.Kofuna ba sa cikin kwaba. ‘Yam mata ba sa kan tabarma. Ba ma hagu da ita. |

‘The cup is not in the cupboard.’ ‘The kola is not between the candle and the bottle.’ ‘You are not in front of me.’ ‘Bashir is not to the right of Bala.’‘The milk is not in the refrigerator.’ ‘You (f) are not between me and Kande.’ ‘The chair is not near the door.’ ‘She is not to the right of you.’‘The cups are not in the cupboard.’ ‘The girls are not on the mat.’ ‘We are not to the left of her. |

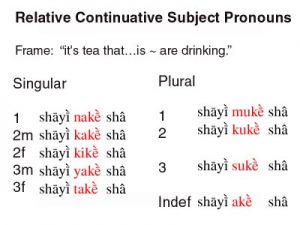

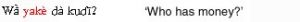

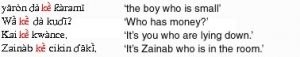

Questioning the Subject of Locative Sentences: ‘what is in the cupboard?”

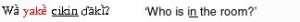

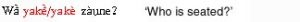

When the subject of a locative sentence is a question word, such as wa? ‘who?’ or me? ‘what?’, the question requires a set of relative continuative pronouns ending in -ke similar to those that are used with verbs. However, unlike the -ke forms used with verbs, which always have a long e on -ke, those used with locatives are sometimes long and sometimes short. The conditions for choosing long -ke vs. short -ke are complex. Examples below avoid the issue by not marking vowel length.

| Wa yake can? Me yake cikin kwaba? Wace ce take kusa da Kande? Su wane ne suke d’aka? |

‘Who is over there?’ ‘What is in the cupboard?’ ‘Who (f) is close to Kande?’ ‘Who all are in the room?’ |

Technical Remarks on the Vowel Length of the Relative Continuative marker –ke

In an important article on the Hausa relative continuative form, Roxana Ma Newman argues that Hausa has two “ke‘s”, a long one and a short one:

Long -ke: This is the form used in relative continuative constructions with verbs. –ke invariably has a long vowel for all speakers in all contexts for the “Kano” dialect, which is the dialect being described here.

Short -ke: This is the form use in sentences without verbs, including ‘have’ sentences, locative sentences, stative sentences, and identificational sentences in some contexts. Complications arise from the fact that “short ke” is sometimes pronounced long! Below are the conditions for “short ke” being pronounced short or long. I give a limited number of examples simply to illustrate the point. See Newman’s paper for more exemplification.

- ke is always short

- ‘have’ sentences with the relative form

- identificational sentences and sentences with adjectival predicates

- In locative sentences before any “true” preposition (a ‘at, in’, daga ‘from’, ga ‘in the presence of’)

- When the predicate of ANY non-verbal sentence has been placed at the front of the sentence for emphasis.

- ‘have’ sentences with the relative form

- ke is always long

- When the pronoun part of the –ke construction is omitted following an over subject

- In locative sentences with “specific” locational words ending in the linker –n

- When the pronoun part of the –ke construction is omitted following an over subject

- ke varies as long or short from speaker to speaker

- With stative predicates

- With locative predicates which do NOT begin in a “true” preposition (a ‘at, in’, daga ‘from’, ga ‘in the presence of) or a “specific” locational word ending in the linker –n.

- With stative predicates

Reference

Newman, Roxana Ma, “The two relative continuous markers in Hausa,” in L.M. Hyman, L.C. Jacobson, and R.G. Schuh (eds.), Papers in African Linguistics in Honor of Wm. E. Welmers, Studies in African Linguistics, Supplement 6, pp. 177-190, 1976.

Footnote

There are several reasons for keeping “short ke” separate from “long ke“, even when “short ke” is pronounced long. First, in Western dialects, the two are completely distinct–the “short ke” is always short, the form corresponding to Kano “long ke” is always pronounced ka, and there is no “long ke“. Second, the context where ALL speakers pronounce “short ke” as long has an explanation. This is the context where the pronominal agreement ya ‘he’, ta ‘she’, su ‘they’ is omitted when an overt subject is present. If ke is considered to be a suffix to the pronoun, then it obviously cannot be pronounced short since there is no pronoun for it to be suffixed to! Third, in other contexts where “short ke” is pronounced long, there is variation among speakers, some pronouncing it long, some pronouncing it short, whereas ALL speakers ALWAYS pronounce “long ke” long. Since we are attempting to describe the Hausa LANGUAGE rather than the speech of a single individual, we can make sense of the variation by saying that the base form is “short ke“, which is pronounced long by some speakers in some contexts. (An alternative would be to speak of different distributions of long and short ke in different dialects, though Newman points out that one cannot even delimit “dialects” for this variation, since speakers who have grown up in the same place may vary in their use of ke.)

Questioning the location in Locative Sentences: ‘where is the cup?’

When the location of a locative sentence is a question word, usually ina? ‘where?’ the question can take one of several forms. A basic question asking where a person or thing sought is has three variants:

| [preposition a ‘at’ +] ‘where’ (+ thing sought) + relative continuative pronoun

[see green note below] |

A ina kofi yake? A ina yake? A ina kuke? |

‘Where is the cup?’ ‘Where is it?’ ‘Where are you?’ |

| (thing sought +) plain continuative pronoun + ‘where’ | Kofi yana ina? Yana ina? Kuna ina? |

‘Where is the cup?’ ‘Where is it?’ ‘Where are you?’ |

| ‘where’ + thing sought | Ina kofi? | ‘Where is the cup?’ |

*Note: The preposition a can be omitted in the first type of phrase above, but among Kano speakers at least, there is a strong preference to use it. However, a is never used in the last type of question, where the relative continuative pronoun is absent.

The last variant in the table above is available only when the thing sought is a noun.

If the questioned location is a phrase, the whole whole phrase must be at the beginning of the sentence if it has a “true” preposition (a ‘at, in’, daga ‘from’, ga(re) ‘in the presence of’), but if the “preposition” is one of the “specific” locational words, the entire phrase may be at the beginning or just the question word, with the locational word left at the end. The relative continuative pronouns are required.

| Daga ina kake? Ga wa yara suke? |

‘Where are you from?’ ‘With whom are the children?’ |

| A cikin me madara take? = Me madara take ciki?A bayan wa kake? = Wa kake baya(nsa)? |

‘In what is the milk?’ = ‘What is the milk in?’‘Behind whom are you?’ = ‘Who are you behind (him)?’ |

Emphasized Words in Locative Sentences: ‘THE CUP is in the cupboard’, ‘IN THE CUPBOARD is where the cup is’

Locative sentences with emphasized subjects or locations follow the same patterns as the corresponding questions. (See discussion of questioned subjects and questioned locations.) Ne or ce (depending on gender) may follow an emphasized word at the beginning of the sentence.

| Subjects | Kofi (ne) yake cikin kwaba (ba kwano ba). Zainab (ce) take kusa da Kande. |

‘A CUP is in the cupboard (not a bowl).’ ‘It’s Zainab who is near to Kande.’ |

| Locations | A cikin kwaba (ne) kofi yake. Ga Maryam (ne) yara suke. Daga Kano nake. |

‘IN THE CUPBOARD is where the cup is.’ ‘WITH MARYAM is where the children are.’ ‘I am FROM KANO.’ |

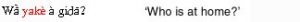

Omission of Pronoun Subject When Noun Subject is Present

If there is a subject word present before the continuative pronoun (plain ending in na or relative ending in ke) the subject agreement part of the pronoun (ya ‘he’, ta ‘she’, su ‘they’, etc.) may be omitted.

| Plain | Amiru yana gida. = Amiru na gida. Maryam tana gida. = Maryam na gida. Mutane suna gida. = Mutane na gida. |

‘Amiru is at home.’ ‘Maryam is at home.’ ‘The people are at home.’ |

| Relative | Wa yake gida? = Wa ke gida? Kofi (ne) yake cikin kwaba. = Kofi (ne) ke cikin kwaba. Kai kake kusa da Kande. = Kai ke kusa da Kande. |

‘Who is at home?’ ‘THE CUP is in the cupboard.’ ‘It’s you who is near Kande.’ |

The ubiquitous expression shi ke nan “that’s all, that concludes the matter” (literally ‘IT is here’) is simply a locative sentence with nan ‘here’ as the predicate and an emphasized subject pronoun shi, which allows the ya- of yake to be omitted.

Sentences Expressing Existence

‘there is tea’, ‘there’s no pounded yam’

Affirmative Existential Sentences: ‘there is tea in the thermos’

Hausa uses an invariable word akwai ‘there is/are…’ to express the existence or presence of something. Akwai alone means ‘there is one, there is some’, as in answer to a question where the object is understood. A more specific location phrase can go before or after the existential construction.

| Q: Akwai shayi? A: Akwai.Akwai shayi a cikin filas. Akwai fensir a kan tebur. A Zango Stores akwai motoci da yawa. |

Q: ‘Is there any tea?’ A: ‘There is (some).’‘There is tea in the thermos.’ ‘There is a pencil on the table.’ ‘At Zango stores there are lots of cars.’ |

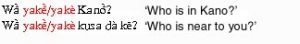

Akwai can take a pronoun object, usually in the sense of ‘one’ or ‘some’. Akwai uses the direct object set of pronouns.

| Q: Akwai kofi a nan? A: Akwai shi.Q: Akwai sakwara? A: Akwai ta. Q: A Zango Stores akwai motoci da yawa? A: Akwai su. |

Q: ‘Is there a cup here?’ A: ‘There is one.’Q: ‘Is there any pounded yam?’ A: ‘There is some.’ Q: ‘At Zango stores are there lots of cars?’ A: ‘There are some.’ |

An alternative to akwai is the preposition da ‘with’. It is also possible to combine the two words, giving da akwai.

| Da shayi.

Da akwai na zinari, da akwai na azurfa. |

‘There is tea.’

‘There are gold ones, (and) there are silver ones.’ |

Negative Existential Sentences: ‘there is no pounded yam’

Hausa uses an invariable word babu ‘there is/are no…’ to express non-existence or non-presence. Babu can be used alone to mean ‘there isn’t any, there aren’t any.’

| Q: Akwai sakwara? A: Babu.Babu d’an kwali. Zango Stores babunisa. |

Q: ‘Is there any pounded yam?’ A: ‘There isn’t (any).’‘There aren’t any head scarves.’ ‘Zango stores isn’t far.’ (“Zango Stores, there’s no distance.”) |

Babu has a short variant, ba, with falling tone on the -a. Ba must always be followed by an object.

| Q: Ina gajiya? A: Ba gajiya.Ba d’an kwali. Ba kome. |

Q: ‘How’s the tiredness?’ A: ‘There isn’t any tiredness.’‘There aren’t any head scarves.’ “That’s OK.” (‘There isn’t anything.’) (Response to an apology.) |

Both babu and ba can take pronoun objects, usually meaning “one, any”. Babu takes the independent form of the pronoun as an object, whereas ba takes the direct object form of the pronoun.

| Q: Akwai sakwara? A: Babu ita.Q: Akwai sakwara? A: Ba ta. |

Q: ‘Is there any pounded yam?’ A: ‘There isn’t any.’Q: ‘Is there any pounded yam?’ A: ‘There isn’t any.’ |

Presenting or Pointing Out

‘here’s my cloth’, ‘there’s Bala’

To say ‘here’s…’ when presenting something to someone or ‘there’s…’ when pointing something or someone out, Hausa uses an invariable word ga ‘here’s…, there’s…’. Ga must always have an expressed object. The ga expression will often be followed by nan ‘here’ or can ‘there’. A ga sentence can include a phrase indicating a specific location.

| Ga kud’in. Ga yadi, na kawo. Ga jakuna nan. Ga Bala can. Ga dutse can yamma da gari. |

‘Here’s the money.’ ‘Here’s cloth, I’ve brought it.’ ‘Here are some donkeys.’ ‘There’s Bala over there.’ ‘There’s a hill to the west of town.’ |

Ga uses the direct object form of the pronoun for pronoun objects.

| Ga shi can bayan kujera. Ga mu nan. |

‘There it is behind the chair.’ ‘Here we are.’ |